Brought to Light

Documents pertaining to the history of Deutsche Bank

The Historical Association is launching an historic document series. The potpourri of documents are a part of Deutsche Bank's corporate history dating back to the Bank's establishment in 1870. Some are of weighty consequence, others are merely something to smile about or to reflect on. An explanatory comment is attached to each document, to help put it into context.

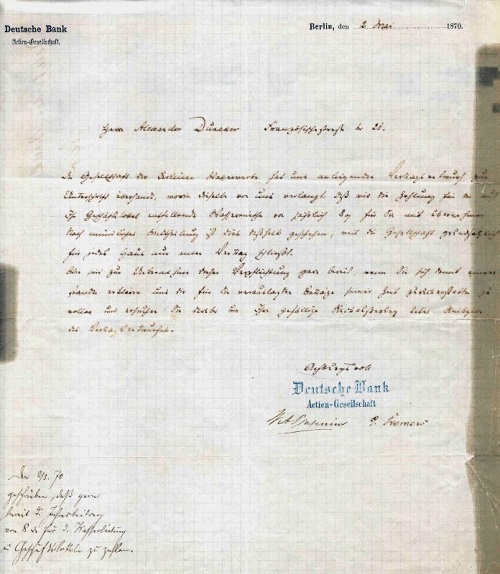

Show content of 02.05.1870 - Once a top priority: a bill from the waterworks

Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank

Actien-Gesellschaft

Berlin, May 2, 1870

To Mr. Alexander Duncker, Französische Strasse No. 21

The enclosed draft contract has been forwarded to us for signing by the Berlin Waterworks, requesting that we settle an outstanding charge of 8 Talers per annum on your behalf to cover the supply of water to your business premises. We were told that this procedure is in accordance with company policy to conclude a new contract for each building.

We shall be pleased to arrange for payment of the said amount, provided you agree to reimburse us in due course for our outlays. May we ask that you return the enclosed contract at your convenience and await your kind reply in this matter.

Yours respectfully,

Deutsche Bank

Actien-Gesellschaft

W. A. Platenius G. Siemens

[Note]

Sent message on 2.5.70 expressing willingness to advance 8 Talers as annual water fee for business premises.

Comment

A mere three weeks after Deutsche Bank first opened the doors of its very modest offices at Französische Strasse 21 in Berlin’s Friedrichstadt district on April 9, 1870, the fledgling enterprise that would later grow to become the country’ biggest bank found itself in the midst of contractual negotiations. The oldest document that bears witness to the beginnings of Deutsche Bank’s business operations was concerned with nothing less than the annual water fee. Together with his (at the time sole) Board colleague, W. A. Platenius, Georg Siemens attended to the matter himself. Given the mere handful of people in the bank’s employ at the time, they were most likely the only authorized signatories anyway. It seems that the two young bankers did not hesitate to advance their landlord 8 Talers to cover the fee charged by the Berlin waterworks for their services – apparently free of interest.

The letter dated May 2, 1870 addressed to Mr. Alexander Duncker, the owner of the premises where Deutsche Bank’s "Head Office" was located, is somewhat of a curiosity by its nature, but it does cast a telling light on the bank’s humble beginnings. Deutsche Bank did not by any means launch its business operations in an imposing new domicile. According to Siemens’ son-in-law, Karl Helfferich, "its first offices were located on the first floor of a decrepit old building on Französische Strasse (No. 21) that had a dingy and hazardous stairway that was by all accounts extremely daunting". But, based on the document, the property apparently did have running water. The landlord, Alexander Duncker, was the owner of the Berlin-based publishing house of the same name. His father, Carl Duncker, was one of the founders of the renowned academic publishers, Duncker & Humblot.

Very little is known about the newcomer bank's first few weeks in business. Siemens’ former colleague, Platenius, later owned up to how little either of them knew about the business at the very beginning. He recalled that they had asked each other: "What do we do now? Do we have any idea of banking?" and that they had both burst into peals of laughter over their own inexperience.

To be fair it should be pointed out that the management team made up of Siemens and Platenius did attend to more weighty matters than water fees in those early days. Just one day later (on May 3, 1870), as documented by the second oldest piece of bank correspondence in our possession, the Board of Managing Directors sent a letter to the Berlin Stock Exchange requesting approval for the forthcoming listing of Deutsche Bank – certainly a step of major import for a joint stock company.

Only a year later the bank and its staff were able to leave their cramped quarters and move to premises of their own on Burgstrasse. The property at Französische Strasse 21 was soon torn down and replaced by a stately new Wilhelminian style building. Today, a section of the Galeries Lafayette complex stands where Deutsche Bank took its first, tentative steps.

Show content of 24.04.1880 - Commemorative leaflet marking the tenth anniversary of the foundation of Deutsche Bank

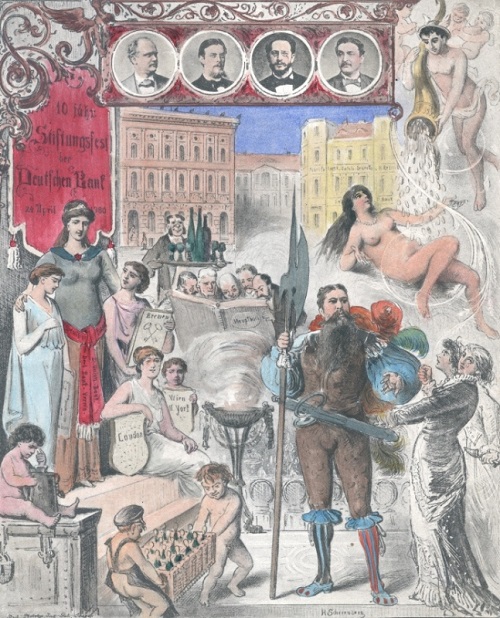

Commemorative leaflet marking the tenth anniversary of the foundation of Deutsche Bank on April 24, 1880

Commemorative leaflet marking the tenth anniversary of the foundation of Deutsche Bank on April 24, 1880

Comment

When setting up a company, it is rare for its founders to think about future anniversaries. Nevertheless, the emerging Deutsche Bank was steeped in the jubilee culture of the Imperial years in Germany. Even the tenth anniversary of its foundation in 1880 was taken as an opportunity to look back on its achievements. This was marked by a colourful commemorative leaflet illustrating the bank’s development to date. The heading of the small hand-coloured lithograph measuring 22 x 18 cm reads “Tenth anniversary of the foundation of Deutsche Bank on April 24, 1880”. It was produced by Hermann Scherenberg (1826-1897), a painter, illustrator and caricaturist.

The illustration he created was composed to include a number references to the first decade of Deutsche Bank’s existence as well as many allegorical figures. Watching over the images are circular portraits of the incumbent Management Board members: Georg Siemens, Rudolph Koch, Max Steinthal and Hermann Wallich. Deutsche Bank’s first three buildings in Berlin can be seen in the background directly underneath them. In the right of the picture, Mercury, distinguishable by his winged helmet, pours from his cornucopia a shower of gold over Danae. An attentive waiter is about to serve wine to the guests. Two putti are carrying a heavy basket full of Champagne bottles. Several bookkeepers can be seen brooding over the bank’s main ledger. The female figures on the left of the picture symbolize Deutsche Bank and its “daughters”, i.e. its branches in Bremen, Hamburg and London as well as its limited partnerships in Vienna and New York. With explicit gestures, a heavily armed Landsknecht is rejecting the advances of two ladies who could be taken to represent the vices of envy and ill-will.

The bank’s 270 Berlin employees were invited by the Management Board to a celebratory dinner at the Hotel Imperial on April 24, 1880. The Spokesman of the Management Board Georg Siemens gave a witty speech, which his wife summarized in a letter to her parents: “He started off with a cheerful account of the foundation, how there had been 24 Administrative Board members, two directors, one clerk and one runner and they had neither money, lodgings nor business; how Koch who had been the clerk back then wrote 50 letters a day stating that all positions had been filled, how Wallich’s constant refrain later on was, “no ideas!”; and in this way they plodded on calmly and grew bigger despite all the turbulence. (….). He underlined the trust between management and staff before finally expressing his hope that this, the best foundation for the Deutsche Bank, may continue to be so for all time.”

Show content of 24.04.1880 - Festive march celebrating Deutsche Bank’s tenth anniversary

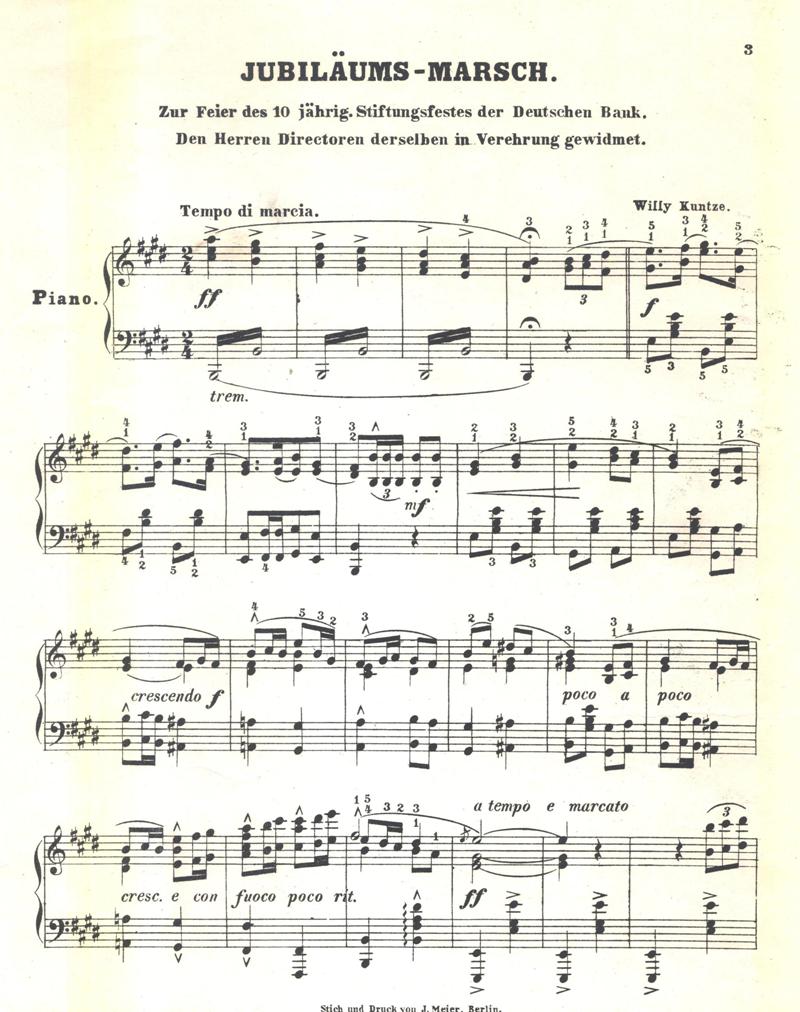

'Jubiläumsmarsch' ( Festive march) celebrating Deutsche Bank’s tenth anniversary,

Festive march) celebrating Deutsche Bank’s tenth anniversary,

‘composed and dedicated – in deepest admiration – to its directors by Willy Kuntze’

A musical score for piano, including the flyleaf

'Jubiläumsmarsch' (audio file)

Comment

Music has a long tradition at Deutsche Bank: from its choral and orchestral societies – both of which had been founded by 1898 – and today’s Deutsche Bank Singers to projects pursued outside the Bank, such as its collaboration with the Berlin Philharmonic. As far back as 1880, however, Deutsche Bank itself had become the subject of a musical composition in the form of a festive march: a four-page score for piano, in E major, played in march tempo and entitled ‘A festive march celebrating Deutsche Bank’s tenth anniversary (1880), composed and dedicated – in deepest admiration – to its directors by Willy Kuntze’. Kuntze was born in Berlin on 14 December 1861 and lived there as a music teacher and composer. His works include pieces for piano and violin as well as 'Lieder' (art songs). He added the following handwritten note on the flyleaf: ‘To Max Netschmann with fond memories, Willy Kuntze.’ Perhaps, by composing this march, Kuntze was looking to offer his services to the Bank’s directors. Or maybe he was giving a present to his friend Max Netschmann, about whom unfortunately nothing is known. It is most unlikely that this was a commissioned work because Kuntze published it himself. He had the music engraving and printing done by J. Meier, a firm based in Berlin. Whether the piece was actually performed is not revealed by the relevant sources. All that remains of the celebrations marking the Bank’s tenth anniversary on 24 April 1880 is a commemorative print, a diary entry by Elise von Siemens, and the invitation to the Bank’s employees (including the menu) – but there is no mention of the march. It is unclear whether it was even played on this occasion. It is possible that the first public performance of the march was when Deutsche Bank’s Historical Institute commissioned Jan Polivka to play it at the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts. Kuntze’s composition borrowed from the song 'Ich bin ein Preuße, kennt ihr meine Farben?' (‘I am a Prussian, know ye my colours?’), which was a sort of unofficial national anthem for Prussia prior to the foundation of the German Empire. The song’s central motif begins after the pause at the end of the prevailing upbeat and is repeated several times during the piece. In using this device, Kuntze was probably emphasising the ‘Prussian character’ of Deutsche Bank, which was headquartered in the Prussian (and subsequently German) capital.

Show content of 04.09.1886 - Deutsche Bank opens a branch in Frankfurt am Main

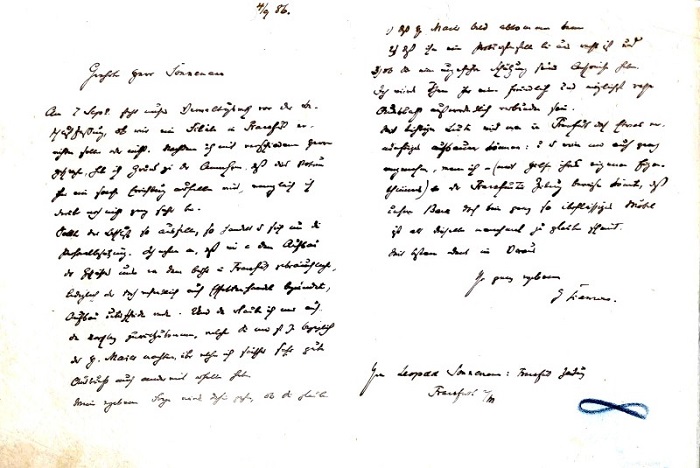

To Mr. Leopold Sonnemann: Frankfurter Zeitung

To Mr. Leopold Sonnemann: Frankfurter Zeitung

Frankfurt a/M“

September 4, [18]86

Dear Mr. Sonnemann,

On September 7th our Board of Directors will adopt a resolution on whether or not to open a branch office in Frankfurt. Following my conversations with various gentlemen, I have reason to believe that a vote will be cast in favour of such a venture, although I cannot be absolutely certain of this.

Should approval be forthcoming, a personnel matter remains to be resolved. I assume that our business operations will differ from customary banking business in Frankfurt which up to now has consisted solely or chiefly of trading in securities. Bearing this in mind, I take the liberty of reverting to the proposal you made a while ago concerning Mr. Maier, whose qualifications have meanwhile been confirmed to me by another source.

May I now take the liberty of inquiring whether you believe

1) that Mr. Maier would be available at short notice and

2) whether he would be willing to assume a position as holder of procuration with our bank and

3) whether you have an approximate idea of what remuneration he would expect to receive.

I would be most obliged to receive your prompt reply.

With local people behind us, we should be able to set up something decent here in Frankfurt. I would also be very gratified to prove to the Frankfurter Zeitung – (with the help of its owners) – that our bank is not quite as useless a fixture as your newspaper sometimes appears to think.

Thanking you in advance, I remain,

Yours respectfully,

G. Siemens

Comment

Deutsche Bank has been a permanent feature in Frankfurt am Main since October 1, 1886 – the date on which the newly established Frankfurt Branch opened its doors at Kirchnerstrasse 3 on Kaiserplatz. Since the bank’s establishment in Berlin in 1870 it was only the third branch office to be opened in Germany, following Bremen (1871) and Hamburg (1872). The branch took over the business operations and premises of Frankfurter Bankverein, which had gone into liquidation. Two experienced bankers were chosen to head the new institution: Carl von Leiden, formerly a member of the Board of Managing Directors of Frankfurter Bankverein, and Wilhelm Seefrid, who left the Board of Privat-Actien-Bank in Danzig to become Director of the Branch in Frankfurt.

Both of these personnel decisions had been taken by the summer of 1886, long before the Board of Directors had taken its final decision on establishing a branch in Frankfurt. In early September 1886, when it was relatively certain that the Board of Directors would give its approval, Georg Siemens, Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors, went about finding a suitable candidate to fill the third and final vacant managerial position. To firmly establish the bank’s position in Frankfurt, he thought it advisable to look for an “insider“ well acquainted with local affairs. On an earlier occasion, the Frankfurt-based newspaper publisher, Leopold Sonnemann, had recommended a certain Mr. Maier to him. Sonnemann, founder and editor of the renowned Frankfurter Zeitung, was a well-known personality, not just in the city of Frankfurt, who also had career experience as a private banker. Siemens and Sonnemann knew each other from time they both served as Members of the Reichstag (1874-1884). The letter shown here dates back to September 4, 1886. In it, Siemens reverts to Sonnemann’s recommendation. Siemens’s Board colleague, Rudolph Koch, had meanwhile made inquiries about Hermann Maier and discovered that he was in the employ of the Bankhaus E. Ladenburg, also based in Frankfurt. He was told that Maier was “an excellent man for dealing with the stock exchange and other businesses in Frankfurt and much better choice than Hoffstadt“, a former director of the recently wound-up Frankfurter Bankverein, who was also being considered for the post. So Koch was very much in favour of appointing Maier to the position. Siemens reason for writing Sonnemann was to inquire whether Maier would be available to join the bank at short notice, whether he would be satisfied with a post as an authorized officer and what his salary expectations would be. The letter reached Sonnemann in the Belgian seaside resort of Ostende, where he was vacationing. He wrote Siemens a telegram in reply: “Believe both questions can be answered affirmatively, best to discuss further details directly with Maier.“

Things moved quickly from there. On September 7, 1886 the Board of Directors decided to go ahead with the plans to establish a branch in Frankfurt, which was opened to the public only three weeks later. On board from the very start was the man for whom Sonnemann had put in a good word. As it turned out, hiring Hermann Maier was a stroke of luck for the newly established branch. Initially in charge of stock market, foreign exchange and foreign trade business, Maier was made Deputy Managing Director after only four years. In 1899 he became Managing Director of Frankfurt Branch - a position he was to hold right up to his retirement in 1912. Much of the credit for the bank’s quickly overtaking its competitors to become one of the leading addresses at the Frankfurt financial centre went to Hermann Maier. So Board Spokesman Georg Siemens could easily have proven to Leopold Sonnemann and the editors of Frankfurter Zeitung, who were initially highly critical of the newly founded Deutsche Bank, that the bank was not ”quite as useless a fixture“ as the paper at times seemed to think.

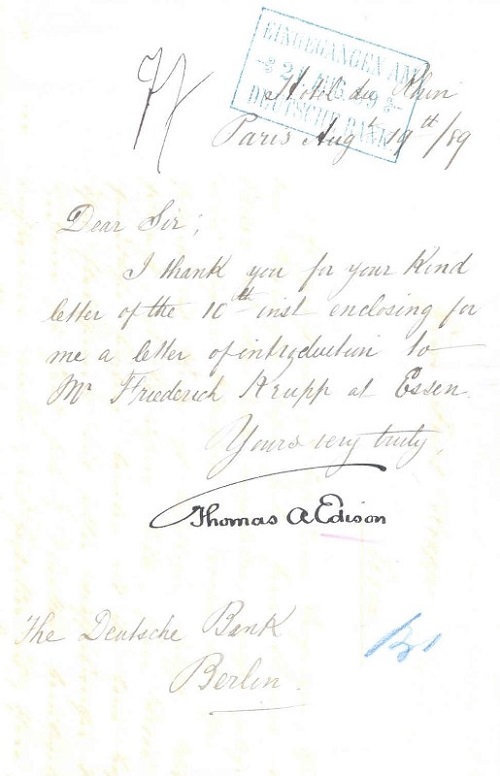

Show content of 19.08.1889 - Edison visits Krupp or how Deutsche Bank's communication system worked

The Deutsche Bank Berlin

The Deutsche Bank Berlin

Hotel du Rhin, Paris Aug 19th [18]89

Dear Sir,

I thank you for your kind letter of the 10th inst enclosing for me a letter of introduction to Mr Frederick Krupp at Essen.

Yours very truly

Thomas A Edison

Comment

From the very beginning, banks have served business and industry not just as money lenders, but have frequently also helped to foster communications. A good example is the short handwritten note shown above, which the American inventor and entrepreneur Thomas Alva Edison addressed to the Berlin office of Deutsche Bank in August 1889. By that time, the only 42-year-old "father" of the first commercially practical light bulb had already achieved fame on both sides of the Atlantic. He had first presented his carbonized filament lamp to a broad public at the International Exposition of Electricity in Paris in 1881, launching it on the road to success. To market his patents in Germany, Edison had founded a company known as Deutsche Edison Gesellschaft – which became AEG in 1887– and this had brought him into contact with Deutsche Bank, which was showing a growing interest in the newly established electrical industry.

Henry Villard, an American financial magnate of German origin, who served as a financial consultant to Edison, had arranged the contacts. It was also Villard who approached Deutsche Bank in the summer of 1889, informing the bank's Board that Edison was coming to Europe to visit the World Exhibition in Paris and would subsequently be travelling to Berlin. On the way, Edison was hoping to tour the Krupp works in Essen. Deutsche Bank, known to have good business relations with Krupp, was asked to write a letter of introduction to open the right doors.

It was not by chance that Edison was interested in Krupp. The German weapons manufacturer whose rear-loading field gun dominated the world market already had a legendary reputation in those days. But the company also produced heavy industrial goods, such as crankshafts, rails and other railway material, as well as boiler plate and shipbuilding plate.

Deutsche Bank was only too pleased to take action on Mr. Edison's behalf. Krupp was approached without delay, requesting that "Mr. Edison be afforded a cordial reception and be supplied with all requested information during his visit to your establishment." By return post, the Krupp Board of Directors in Essen replied that they would be very gratified to show Mr. Edison their cast-steel works. This put Deutsche Bank Berlin in the pleasant position of being able to send the desired letter of introduction to Hôtel du Rhin in Paris, where "the celebrated father of electric lighting" was staying. As an expression of his gratitude Edison sent the above note on August 19, 1889.

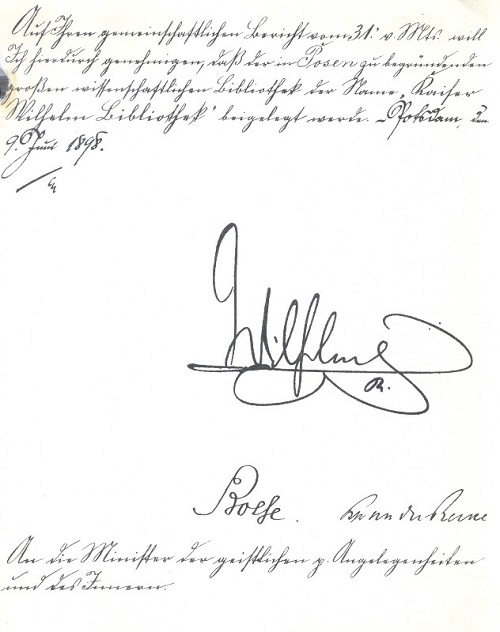

Show content of 09.06.1898 - A Donation for the Emperor’s Library in Posen

An die Minister der geistlichen p. Angelegenheiten und des Innern.

An die Minister der geistlichen p. Angelegenheiten und des Innern.

Auf Ihren gemeinschaftlichen Bericht vom 31. v. Mts. will Ich hierdurch genehmigen, daß der in Posen zu begründenden großen wissenschaftlichen Bibliothek der Name „Kaiser Wilhelm Bibliothek“ beigelegt werde.

Potsdam, den 9. Juni 1898.

Gez. Wilhelm R.[ex] Bosse [Preuß. Kultusminister] Frhr von der Recke [Preuß. Innenminister]

Comment

The city of Poznan, located in the middle of present-day Poland, was the capital of the Prussian province of Posen a hundred years ago. The province was inhabited mainly by Poles, who also made up 50 per cent of the population of the city of Posen. The 3.7 million-strong Polish ethnic group constituted the largest minority in the German Empire. Their “Germanization“ was a declared aim of German policy, carried out by means of wide-scale intervention into agricultural land ownership and attempts to suppress the Polish language and culture.

The foundation of a German scholarly library in Posen, as resolved by the Imperial Government in 1898, was intended to serve this very purpose. The Government also put forward a proposal to have the library named after Emperor William I – a request that was subsequently granted by his grandson, Emperor William II, in the Prussian Cabinet Order depicted here.

So the plans had been laid and a name found – but the funding was still lacking. A committee was consequently set up and Erich Liesegang, Head of the Royal Library and Professor in Berlin, was assigned the job of fundraising. In April 1899 Liesegang put in an appearance at Mauerstrasse, where the Head Office of Deutsche Bank in Berlin was located. He asked for an appointment with the Spokesman of the Board, Georg Siemens, to draw his attention to the “grand national cause“ of the Emperor Wilhelm Library in Posen and request a donation. He presented the Prussian Cabinet Order signed by William II in the Board Secretariat to underscore the official nature of his mission.

Siemens declined to meet Liesegang on the grounds of other pressing commitments; on the whole, however, it was apparent that the undertaking went against his grain. On the subject of his visitor and the purpose of his visit Siemens wrote: “His sights are apparently not set on the 100 Marks he could pry out of me, but on a larger donation from DB. I do not see DB having an interest in this matter. We are not national, but international – the fear of Poland, i.e. the fear of the Empire being dominated by a weak minority, appears rather unfounded to me.“ These few, succinct words reveal the broad-minded attitude of the man who at the time had spent 29 years at the helm of an enterprise founded for the purpose of „promoting and facilitating trade relations between Germany, the other countries of Europe and overseas markets“. Siemens was always a liberal thinker, both in economic and political terms, who did not share the nationalistic views of his contemporaries.

His Board colleague, Arthur Gwinner, was more inclined to make concessions to the Zeitgeist, as can be seen from his comments on the question of making a donation: “Though I am of the opinion that the Germanization of the Polish provinces is an important task for the German nation, I do agree with Dr. Siemens that Deutsche Bank does not have the funds for this purpose. I personally would be glad to donate 100 Marks.“

In Deutsche Bank’s official letter of reply Siemens informed Professor Liesegang that, “legal stipulations and company statutes prohibit Deutsche Bank from using shareholder funds for projects of this nature which are outside the bank’s statutory scope of business.“ Enclosed with the letter were two cheques, one for 50 Marks and one for 100 Marks, representing personal donations made by Siemens and Gwinner respectively to the library building project. Those amount were not as negligible as they may appear today – back then 100 Marks corresponded to about half the monthly salary of an average bank employee. These private donations were an elegant way of getting round the matter without compromising the bank.

The library in Posen was opened in September 1902. Emperor William II made the long journey to the city on the River Warthe for the occasion. Today the building, constructed by architect Karl Hinkeldeyn in Late Renaissance style, houses the library of the University of Poznan.

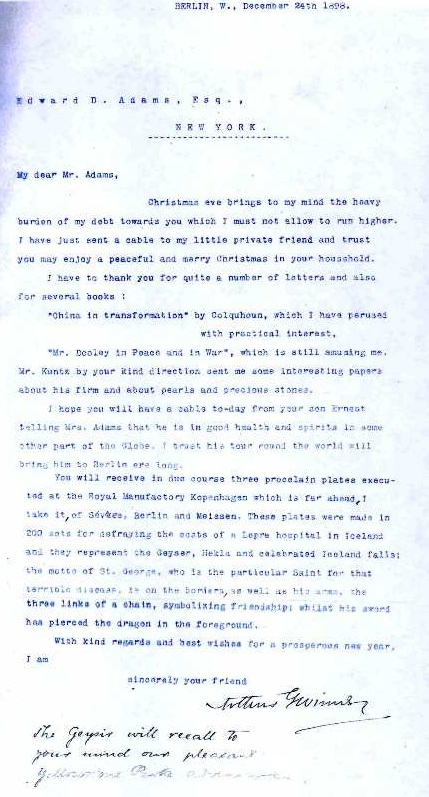

Show content of 24.12.1898 - Greetings to our man in the United States

Berlin, W., December 24th 1898.

Berlin, W., December 24th 1898.

Edward D. Adams, Esq., New York

My dear Mr. Adams,

Christmas eve brings to my mind the heavy burden of my debt towards you which I must not allow to run higher. I have just sent a cable to my little private friend and trust you may enjoy a peaceful and merry Christmas in your household.

I have to thank you for quite a number of letters and also for several books:

‘China in transformation’ by Colquhoun, which I have perused with practical interest,

‘Mr. Dooley in Peace and War’, which is still amusing me.

Mr. Kuntz by your kind direction sent me some interesting papers about his firm and about pearls and precious stones.

I hope you will have a cable to-day from your son Ernest telling Mrs. Adams that he is in good health and spirits in some other part of the Globe. I trust his tour round the world will bring him to Berlin ere long.

[…].

You will receive in due course three porcelain plates executed at the Royal Manufactory Kopenhagen which is far ahead, I take it, of Sévres, Berlin and Meissen. These plates were made in 200 sets for defraying the costs of a Lepra hospital in Iceland and they represent the Geyser, Hekla and celebrated Iceland falls; the motto of St. George, who is the particular Saint for that terrible disease, is on the borders, as well as his arms, the three links of a chain, symbolizing friendship; whilst his sword has pierced the dragon in the foreground.

With kind regards and best wishes for a prosperous new year,

I am sincerely your friend

Arthur Gwinner

P.S. The Geysir will recall to your mind our pleasant Yellowstone Park adventures

Comment

Edward D. Adams, to whom Deutsche Bank’s Board member Arthur Gwinner sent these cordial season’s greetings, together with a rather original gift of porcelain plates, on Christmas Eve of 1898, was Deutsche Bank’s long-standing representative in the United States. The renowned financial and railway expert began to represent the interests of the Berlin-based financial institution in 1893 and continued to serve as the bank’s loyal representative until 1914.

The close working relationship had begun with a company in distress. To deal with the sudden collapse of the Northern Pacific Railway Company, whose bonds Deutsche Bank had launched on the German capital market, the bank set up a Reorganization Committee, chaired by Edward D. Adams, who managed to work out a plan to rescue the company. Following this successful undertaking, Adams, a man of tremendous energy, meticulous precision and prudence, proved his exceptional organizational talent in managing the affairs of Deutsche Bank in the United States. He not only looked after the bank’s investments on the other side of the Atlantic, he also kept the bank’s management in Berlin informed of ongoing events in the American business world and much more far-reaching topics, as evidenced by the books he sent to Gwinner on the transformation process in China und a humorous collection of newspaper columns entitled “Mr. Dooley in Peace and War“, for which Gwinner expresses his gratitude in the above Christmas letter.

Gwinner’s held Adams in high esteem as a “clear-headed and precise worker“ and thought him absolutely reliable, even if he was, in the Deutsche Bank Board member’s opinion, ”a bit sensitive, or touchy, as the English say, and very keen to be taken into one’s trust and receive acknowledgement thereof."

As the warm and cordial tone of the letter shows, Adams and Gwinner were more than mere business acquaintances. They shared a genuine friendship that was enhanced by Adams’ regular visits to Germany. At the time, letters, telegrams and parcels were sent back and forth between New York and Berlin almost daily. The number of letters exchanged went into the thousands. They always corresponded in English, a language in which Gwinner, having spent four years in the City of London early in his career, was fluent.

In summer of 1896 Gwinner traveled to the United States, where, assisted by Adams, he conducted negotiations on railway investments with the legendary New York banker, John Pierpont Morgan. Gwinner took this opportunity to learn more about the country. Accompanied by Adams, he first traveled from New York to Chicago, and from there further west. In Wyoming he visited the already famous Yellowstone National Park, and refers to the park’s main attraction both in the post scriptum to his Christmas letter as well as in his memoirs. Describing the grand natural spectacle, he writes: ”The geyser erupts, spewing huge masses of boiling water up to 100 feet into the air and producing greats clouds of snow-white steam. Set against the deep-blue sky (– the park lies at roughly the same altitude as the Engadin region [of Switzerland] –) theses bursts of steam are indeed a breathtaking spectacle, far more picturesque than any painting could ever hope to render.“

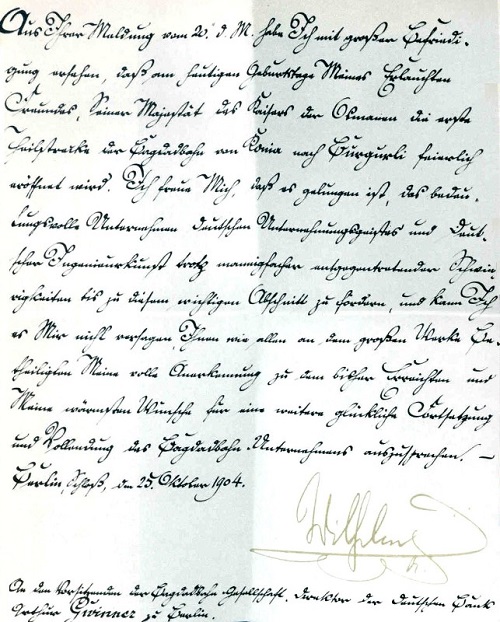

Show content of 25.10.1904 - First section of the Baghdad Railway opened

To Arthur Gwinner, Chairman of the Baghdad Railway Company and Director of Deutsche Bank, Berlin.

To Arthur Gwinner, Chairman of the Baghdad Railway Company and Director of Deutsche Bank, Berlin.

I was deeply gratified to learn from your statement of October 20th that the official opening of the first section of the Baghdad Railway line from Konya to Burgurli will take place today, on the birthday of my highly esteemed friend, His Majesty the Emperor of the Ottoman Empire. I am pleased that, despite the many difficulties encountered, this significant project, which serves as an outstanding example of the German spirit of enterprise and German engineering skills, has now entered this key phase of its development. Therefore I cannot but commend you, and all those involved in this grand endeavour, for all that has been accomplished thus far, and extend my warmest wishes for continued success in the completion of the Baghdad Railway Enterprise. –

Berlin, Palace, October 25, 1904.

Wilhelm

Comment

On October 25, 1904 Arthur Gwinner, Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors of Deutsche Bank and Supervisory Board Chairman of the Baghdad Railway Company, received a letter from Emperor William II, congratulating him on the official opening of the first 200 kilometres of the Baghdad Railway, from Konya, in Central Anatolia, to Burgurlu, at the foot of the Taurus Mountains. This first stretch was completed in less than a year.

The Baghdad Railway was undoubtedly the most spectacular business venture undertaken by Deutsche Bank prior to World War I, a project to which it gave both financial and operational backing. No other undertaking was as controversial and much contended as this railway line, due to run from Haydarpasha Station in the Asian section of Istanbul all the way to the Persian Gulf.

The initial momentum for the project goes back to 1888 when Sultan Abdul Hamid II approached German financial circles, requesting their support for his plans to strengthen his country’s economic and strategic position by building a railway across the huge Turkish empire from the Bosporus to Shat Al Arab region. After overcoming its initial scepticism, Deutsche Bank later agreed to take part in the project. In October 1888 the bank was awarded the concessions needed to build the initial stretch from Haydarpascha to Ismid, and from there to Ankara.

The building and operating concession for the railway project was transferred to the Anatolian Railway Company, a joint-stock enterprise established under Turkish law for this very purpose. The majority of the company’s shares were held by Deutsche Bank.

Construction work was carried out primarily by the Frankfurt-based building contractor, Philipp Holzmann. Despite difficult topographic conditions, work proceeded quickly and so the nearly 600 kilometre stretch to Ankara was completed by the end of 1892. Four years later, in 1896, it reached the city of Konya, some 400 kilometres further along the line.

The following years were taken up by negotiations on extending the railway from Konya to Baghdad, and from there to the Persian Gulf. Long-winded disputes ensued with Europe’s Great Powers who regarded the railroad as a threat to their political and economic interests. The Baghdad Railway was the subject of public debate time and again. "I’m fed up with this concession and the whole Baghdad Railway", said an irate Georg von Siemens, Deutsche Bank’s Board Spokesman in 1898. Plagued by the many political obstacles being placed in his way, he was so annoyed with the entire project that in early 1899 he offered it to the Russian Minister of Finance, Sergey Witte, who politely declined.

Finally, in March 1903, Deutsche Bank signed an agreement, known as the Baghdad Concession, granting permission for the railway be to continued – in 200 kilometre stages – from Konya, via the Taurus and Amanus Mountains, to Mosul, Baghdad and Basra. At the outbreak of World War I, roughly 600 kilometres had been completed, leaving another 650 kilometres to go before reaching Baghdad. Wartime turmoil and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire brought construction work on the railway to a complete standstill. Two decades later, in the years from 1936 to1940, the Iraqi government finally had the railway line to Baghdad completed. The first passenger train to leave Istanbul en route to Baghdad started its maiden journey on July 15, 1940.

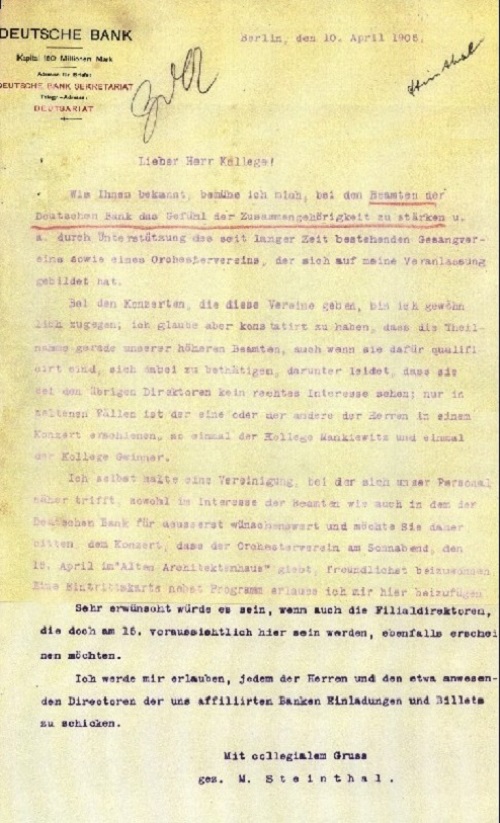

Show content of 10.04.1905 - “An opportunity for our staff to enhance their personal contacts“ - Deutsche Bank’s choir and orchestra

To Director MICHALOWSKY

To Director MICHALOWSKY

- in the bank -

Berlin, April 10, 1905

Dear colleague,

As you are surely aware, I took the initiative to establish a choral society and an orchestral society in the bank some time ago. I continue to support them in an attempt to foster a spirit of companionship among the officers of Deutsche Bank.

As I regularly attend the concerts given by these associations, it has come to my attention that very few of our culturally inclined senior officers are to be found in the audience. It would appear that their enthusiasm suffers from the lack of true interest on the part of the other directors, who seldom grace our concerts with their presence. Our colleagues Mankiewitz and Gwinner have been known to attend on one occasion each.

Personally, I believe that this opportunity for our staff to enhance their personal contacts is very much in the interest of both our officers and Deutsche Bank itself. I would therefore be greatly obliged if you could attend the concert being given by the orchestral society in ‚Altes Architektenhaus’ on Saturday, April 15. I take the liberty of enclosing an admission ticket and the programme.

It would also be greatly appreciated if the Branch Directors, who to my knowledge will also be in the city on the 15th, could show the courtesy of coming. I will take the liberty of sending invitations and tickets to each of the gentlemen and any directors of affiliated banks in Berlin on that date.

Respectfully yours,

signed M. Steinthal

Comment

In April 1905 Max Steinthal (1850-1940), Member of the Board of Managing Directors of Deutsche Bank since 1873, decided the time had come to voice his displeasure. He was annoyed that his board colleagues, known as Directors at the time, failed to show a sense of corporate identity – at least where the cultural pursuits of their employees were concerned. Both the choral society and the orchestral society of Deutsche Bank had been founded on Steinthal’s initiative. Established in 1900, these two cultural societies for vocally and musically inclined Head Office staff were funded by a foundation Steinthal set up in 1898, raising its assets twice in later years.

Steinthal remained a loyal sponsor over the years and often made generous donations. The revenues earned by the foundation were used to buy sheet music, cover concert overheads and pay the fees for (outside) conductors.

In the early years of their existence, mentor Steinthal felt that the bank’s other top executives failed to take sufficient note of the two fledgling societies. That was what prompted him to personally approach Carl Michalowsky, his board colleague responsible for personnel matters. In a letter dated April 10, 1905, Steinthal brought his attention to the forthcoming concert that was to feature pieces of music by Beethoven, Brahms, Johann Strauss (naturally including the “Blue Danube Waltz“), Boccherini and some lesser composers such as Moszkowsky and Wieniawsky.

Regrettably, there are no records of Michalowsky’s response, nor it is known whether similarly blunt letters were sent to other board colleagues encouraging them to show greater enthusiasm. The fact is that both the bank’s choir and orchestra unfailingly continued to build a corporate identity. Only the onset of the First World War brought their musical endeavours to a halt for a while.

On the 25th anniversary of the choral and orchestral societies, the Board of Managing Directors donated a Bechstein grand piano in recognition of their work. The bank’s employee magazine, first published in October 1927, devoted a regular column to the latest pursuits of both choir and orchestra. Following the example of the Head Office in Berlin, employees at the Cologne and Breslau Branches established their own choirs in October 1927 and January 1928, respectively.

Both the Head Office vocalists and instrumentalists held their rehearsals on the premises of the bank’s own Officers Club located on Behrenstrasse. After the merger with Disconto-Gesellschaft, which had had a choir of its own since 1897, the vocal ensembles of the two banks were joined together.

Under the Nazi regime, news about the societies became more and more sparse. The last record mentioning the choir and orchestra of Deutsche Bank is an announcement of a gala concert in October 1940, commemorating the 40th anniversary of the male choir (as the choral society was meanwhile known). The Second World War later put an end to the staff concerts – they were not resumed after 1945.

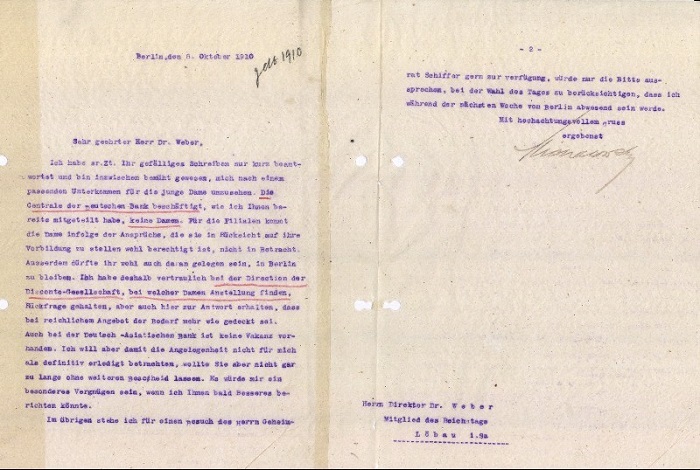

Show content of 08.10.1910 - "An appalling smell of violets": women’s first ventures into banking

Dear Dr. Weber,

Dear Dr. Weber,

As I was previously unable to send more than a brief reply to your kind letter, I would now like you to be informed that I have made inquiries on behalf of finding appropriate employment for the young lady in question. As you know, the Head Office of Deutsche Bank does not employ ladies. As regards our branch offices, I fear that a position commensurate with her fine educational background is not available there. Moreover, I assume that it is her intention to remain in Berlin. I approached the Board of Directors of Disconto-Gesellschaft, which has ladies in its employ, but they, too, replied that they already had more applications than available placements. Nor was an opening to be found at Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. You may rest assured that I am not regarding the matter as closed, but I did not want to leave you waiting any longer. It would give me great pleasure to be able to furnish a more positive reply in the near future.

As concerns the question of a visit from Privy Councillor Schiffer, I shall be pleased to be at his disposal. When arranging a date for his visit I would ask you to kindly bear in mind that I shall not be in Berlin next week.

Yours faithfully,

Michalowsky

Comment

“The Head Office of Deutsche Bank does not employ ladies", was the lapidary way Carl Michalowsky, Board Member responsible for personnel matters, responded in 1910 to a request from banking colleague and Member of the Reichstag, August Weber, inquiring into the possibility of employing a “young lady“. Apparently the candidate in question had good academic qualifications, which was quite exceptional at the time since women had only been given the right to attend university a few years before. It would seem, however, that her very qualifications barred her from finding an appropriate position with a bank. If at all, women were only hired for unskilled, low-wage jobs, such as operating the newly introduced typewriting machines that were finding their way into more and more offices, thereby rendering obsolete the traditional (male) profession of chancellery scribe.

Against this background, most male bank employees were rather hostile to the idea of women joining the banking profession. Comments condemning some local big banks for the "highly objectionable practice of hiring womenfolk” reflect the sentiment prevailing in the industry prior to the First World War. So it hardly comes as a surprise that up to the mid-1920’s the banking profession remained very much a male preserve. It was not until demand for office staff increased in the course of the First World War and the subsequent period of high inflation that a greater number of women started entering the banking world – mainly as auxiliary staff needed to run the growing numbers of office machines being introduced with advancing automation. Between 1875 and 1907 the percentage of women among bank employees in Germany rose from 0.7% to 5.5%, and by 1925 had reached a substantial 21%. Two years later, in 1927, Deutsche Bank had 8,363 men and 2,082 women on its payroll and employed 711 male and 150 female apprentices at its Head Office and branches. However, there was not a single woman to be found in its 1,245 management positions.

The “old school” of bankers and their associations were particularly vehement in trying to prevent women from invading their profession. Among the arguments launched against women in the labour force were claims that the office air would be bad for women’s health, that they couldn’t work as hard as men and lacked the necessary intelligence and ambition, and that they were merely a form of cheap labour undercutting their wage levels. Besides these far-fetched notions, some male colleagues even lodged bizarre complaints about “the appalling smell of violets” in the office.

The German Association of Bank Employees flatly refused to admit women members and was still hostile to women in the workplace as late as 1915, when it issued the following official statement: “In the interest of our profession we will always support the view that the employment of women in banks is to be discouraged at all costs, and it can only be in the best interests of the banks themselves to leave the running of their business to the men, instead of organizing the bank like some kind of a department store.”

Show content of 30.10.1915 - "They crammed 880 people into 10 wagons"

Black and white photograph on paper, 11.9 cm (wide) x 8.9 cm (high), punched top left, filed in a binder of the Deutsche Bank Head Office Berlin's Orient Department entitled "Armenian Question during the War".

Current classification: HADB, Or1704, enclosure to page 50.

Commentary

On 30 October 1915, Franz Günther, the director of the Anatolian Railway Company based in Constantinople, wrote to the chairman of the railway company's supervisory board, Arthur von Gwinner, who was also the spokesman of Deutsche Bank's Management Board in Berlin:

"Dear Mr. von Gwinner, I am enclosing a small picture showing the Anatolian Railway as a bearer of culture in Turkey. These are our so-called mutton cars, in which, for example, 880 people are transported in 10 cars." (HADB, Or1704, page 50)

The picture shows three small livestock wagons, which can be clearly assigned to the Anatolian Railway by the acronym "C.F.O.A." (Chemin de Fer Ottoman d'Anatolie). It is clearly visible that far more than the 40 people stipulated by the wagon inscription "40 HOMMES" were crammed onto the two levels and the roof of each wagon. When and where the photograph was taken is unknown, as is the photographer.

Even though it can be assumed that Günther knew the originator of the picture, it is hardly surprising that he passed it on anonymously, as photographing Armenian transports was prohibited under penalty of law. After Turkish military personnel learned that engineers and employees of the Baghdad Railway had taken photos of Armenian transports, the military commander in Syria, Djemal Pasha, issued an order that these individuals had to hand over the negatives and all prints of their photographs to the military commissariat within 48 hours. Anyone who refused to surrender the photos was to be punished as if they had taken photos of war scenes. (Military Commissar to Construction Department III of the Baghdad Railway 28.8./10.9.1915, PA-AA/BoKon/70) The photograph forwarded by Günther is therefore extremely rare.

Another letter from Günther to Gwinner, which had already been sent to Berlin on 14 October 1915, allows for a conjecture as to where the photo might have been taken. It states – supplemented only by the location – almost verbatim with his later letter: "From Alajund to Konia - 369 km - the police loaded Armenians into our so-called sheep wagons; these are usually freight cars that are divided horizontally in the middle by slats. They crammed 880 people into 10 wagons, i.e. 88 heads per car." (HADB, Or1704, pages 32f.) Alajund was a small railway station, 67 kilometers south of Eskischehir, where a siding line to the nearby town of Kutahia branched off from the main line to Konia. According to a report by an unnamed traveller, presumably a representative of the company responsible for the railway construction, from October 1915, there was "an Armenian camp of enormous size in Alajund, which certainly housed several thousand people". The same traveller observed a scene in Eskischehir that is strongly reminiscent of the photo described here: "The deportees were partly housed in small livestock wagons (sheep wagons) on both levels, the roofs of the wagons were also covered with people." (HADB, Or1704, pages 54-62) Günther sent this report to Gwinner together with the photo. Another copy, but without the photo, went to the chargé d'affaires of the German embassy in Constantinople, Konstantin von Neurath. (PA-AA/BoKon/97) The "reliable gentleman", as Günther called the author of the report in his accompanying letter, was possibly also the photographer of the described transport in the sheep wagons. The locations he and Günther mentioned in connection with the Armenian transports suggest that the photo was taken in Eskischehir or at the nearby Alajund station. If the unknown author of the report was the photographer, then the picture must have been taken during his journey, which ended in Constantinople in October 1915 and took him to the furthest point of the railway to Ras-el-Ain – halfway between Aleppo and Mosul.

The letter from Günther to Gwinner dated 15 October 1915 was first quoted in Gerald D. Feldman, The Deutsche Bank from World War to World Economic Crisis 1914-1933, in: Lothar Gall et al., The Deutsche Bank 1870-1995, London 1995, p.142. The photo was first published in Manfred Pohl, Von Stambul nach Bagdad. Die Geschichte einer berühmten Eisenbahn, Munich 1999, p. 94.

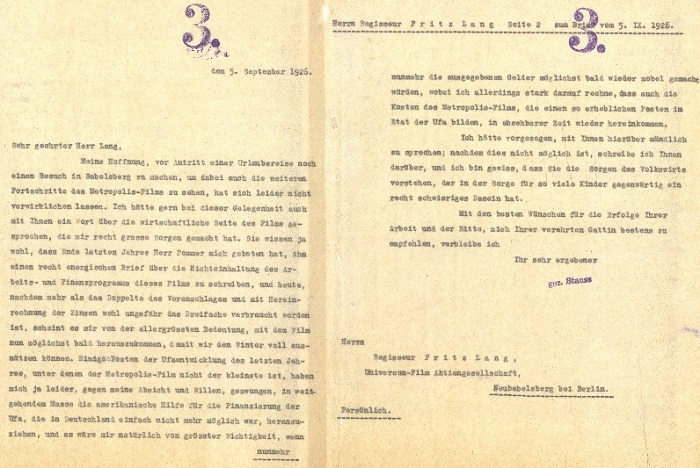

Show content of 05.09.1926 - Deutsche Bank’s role in Fritz Lang’s landmark film “Metropolis“

Mr. Fritz Lang

Mr. Fritz Lang

Director

Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft

Neubabelsberg near Berlin

-PERSONAL-

September 5, 1926

Dear Mr. Lang,

I had hoped my schedule would permit me to visit Babelsberg before my holidays to see how the Metropolis production is coming along, but I’m afraid things have turned out otherwise. I would have liked to have had a word with you concerning the financial side of the film, which is causing me a good deal of concern. As you will surely recall, Mr. Pommer asked me write him a forthright letter at the end of last year regarding the failure to comply with the film’s shooting schedule and financial programme. Today, after using up more than double the estimated resources – or even triple, if one includes accrued interest – it is of prime significance that the film be released as quickly as possible, so that we can make full use of the coming winter. This last year, a number of items in Ufa’s business development, in which the Metropolis production plays no small part, have forced me, contrary to my intention and volition, to seek American financing assistance for a number of Ufa projects, since it was simply impossible to obtain such funding in Germany. So you will certainly understand that it is of utmost importance for the funds that have been spent to be recovered as soon as possible. Of course I firmly count on the Metropolis production costs, which feature so prominently in the Ufa budget, being recouped in the foreseeable future.

I would have preferred to speak with you personally in this matter, but as that is not possible, I am writing you in the certainty that you will understand the concerns of an economist whose life is currently being rendered rather difficult by the many children in his care.

With my very best wishes for the successful outcome of your work, and my kindest regards to your esteemed wife, I remain,

Yours faithfully,

Stauss

Comment

The epic film Metropolis, released in 1926, is a milestone in cinema history. Probably the most famous film directed by Fritz Lang, the idea for the screenplay was born on a trip to the United States. As his ship entered New York harbour, he was so deeply impressed by the skyscrapers looming out the sea that he chose a utopian, high-rise cityscape as the main setting for his cinematic vision of class struggle in the 21st century.

Metropolis was ground-breaking not only in terms of its monumental imagery, novel animation techniques, huge numbers of performers and futuristic scenario. It also set a new record in terms of production costs for the film’s production company, Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa), in which Deutsche Bank not only had a substantial holding, but whose director, Emil Georg von Stauss, also served as Chairman of the Supervisory Board. To keep Ufa’s financial plight within bounds, film production costs were to be cut back and the budget overruns stopped. When it came to overstepping budgeted parameters, Fritz Lang, a perfectionist striving to realize ever new and more expensive superlatives in his films, eclipsed all others. When his producer, Erich Pommer, realized that the spending for Metropolis was getting out of hand, he turned to Stauss for help. In December 1925 Stauss urged Lang to reduce expenses for studio settings or delete some of the film’s scenes, if necessary. This urgent request, however, had very little effect on Lang. In September 1926, after 16 more months of shooting had passed, Stauss sent the above letter to Lang, demanding in no uncertain terms that the film be brought to a conclusion soon. In the interim, production costs had risen to three times the originally calculated expenses and the Ufa studios had take up a loan in the USA to keep from going out of business. But that did not harm Lang’s budding self-confidence which seemed to keep pace with the film’s mounting expenses. In his reply, he wrote Stauss that Metropolis would be finished very shortly and that he was certain “that not only will Ufa studios reap top accolades for this film around the world, but will also recoup the capital invested in it together with interest and compound interest.“

Though Lang turned out to be correct in terms of the film’s artistic value, the banker’s scepticism proved more realistic than the film-maker’s optimism on the financial side. The film’s box-office proceeds did not manage to cover the 5.3 million Reichsmarks the epic masterpiece had devoured by the time it was finished. The resulting financial loss was one of the determining factors that prompted Deutsche Bank to give up its stake in Ufa studios in 1927.

Show content of 1927 - "Modern-day banking business” (first advertising film of a German big bank)

"Modern-day banking business" (Der moderne Bankbetrieb)

"Modern-day banking business" (Der moderne Bankbetrieb)

Advertising film for Disconto-Gesellschaft

Year of production 1927

Length 518 meters (approximately 20 minutes)

Comment

The silent film is the first commercial film of a German big bank, produced by the Berlin based Disconto-Gesellschaft in Berlin in 1927. At the time, Disconto-Gesellschaft was in sharp competition with Deutsche Bank. In October 1929, however, the two banks merged to form a joint institution.

The film was made, with the exception of the final sequence, in the head offices of Disconto-Gesellschaft on the boulevard Unter den Linden, which expanded over the Charlottenstraße to the Behrenstraße. The building was sold to the German Reich after the merger. After reunification, Deutsche Bank acquired it. Since 1997, the premises have been extensively restored.

The film starts with street scenes that show the full extent of the building complex. After a glance at the cash hall and the steel chamber, the spectator gets an insight into the back-office areas. The film shows machines that were up-to-date with the latest technology of the 1920s, which was intended to relief employees of monotonous work. The social side of a big bank operation is highlighted in the final sequence 'After Business', which shows the activities of the association of singers and sportsmen.

Production notes that would provide information about the director or cameraman have not been preserved. Nor can it be found in two contemporary reviews of the film - a favorable one in the Disconto-Gesellschaft staff magazine and a critical one in the journal Bankwissenschaft. It is worth noting that the documentary value of the film was already recognized back then: "In a few years' time, it should be considered as a historical document on the appearance of a wholesale bank in 1927 and also of the greatest interest, just as it would be interesting to have a 1900 film report on the way in which the business was done at the time."

On the occasion of the public lecture "The Roaring Twenties" in October 2023, a shortened version of the film was shown, accompanied by pianist Christina Becht.

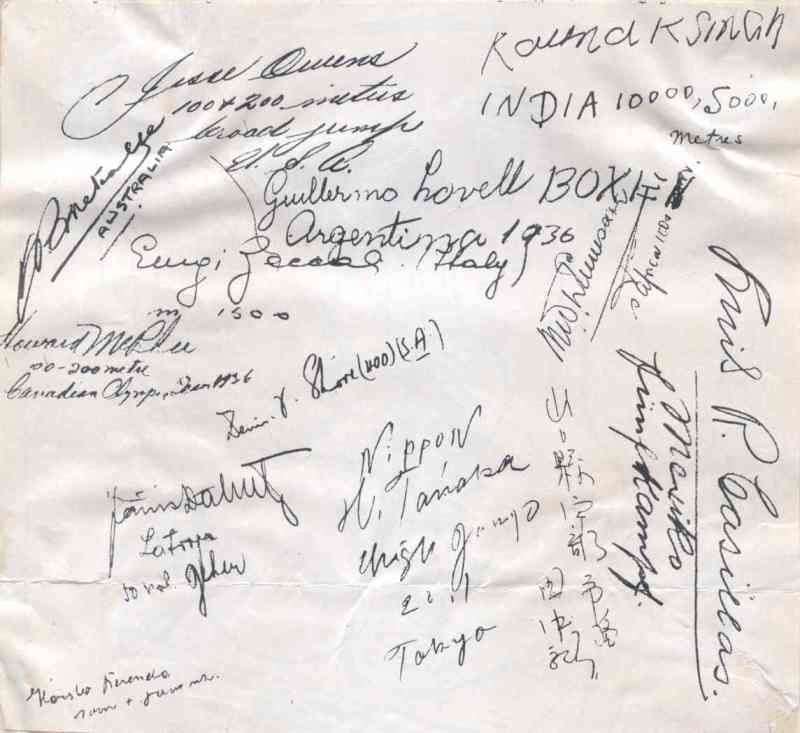

Show content of August 1936 - Third-time Olympic winner Jesse Owens at Deutsche Bank

Jesse Owens 100 + 200 meters broad jump U.S.A.

Comment

The XI. Olympic Summer Games took place in Berlin from August 1 to 16, 1936. A major event that served in the self-presentation of the National Socialist Germany like no other. The athletes and members of the audience from all over the world were to be given a picture of an superbly well organized, prosperous, friendly and peaceful country. Deutsche Bank was also included in the logistics of the Games. Already weeks before they began, the large cashier’s hall of the main city branch in Berlin’s Mauerstrasse was transformed each afternoon at 4:00 p.m. into a sales office for admission tickets. Those waiting in long lines at the 23 counters could buy tickets for all of the Olympic disciplines. On a few days, more than 8,000 sports fans were served by the employees of Deutsche Bank. The staff received express support for their motivation in connection with the Olympics from the bank’s Personnel Director, Karl Ritter von Halt. The former decathlon champion and co-organizer of the Winter Games in 1936 exclaimed to staff members: “Isn’t it magnificent that our bank, too, can work on the success of the Games? Day in, day out, our co-workers are at the counter in the service of the Games and gladly fulfill the tasks entrusted to them.”

Not just in the center of Berlin did the bank stand in the service of the Games, but also in the direct proximity of the Olympic Stadium and the Olympic Village near Döberitz, west of Berlin, where the bank was represented with cashier’s offices to “offer the foreign visitors every convenience possibly conceivable.” In the cashier’s office at the Olympic Village, the athletes picked up their post and cashed their travellers’ cheques and letters of credit. Communicating with the athletes from all over the world did not present any difficulties, because the six employees working in the cashier’s office spoke English, French, Danish, Dutch, Bulgarian, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. The biggest crush at the counters took place when the South American and the last of the European teams arrived shortly before the opening of the Games. Depending on the demand, the cashiers’ hours were extended to 9:00 p.m., and even 11:00 p.m.

By the end of the Games, almost all of the leading figures in sports had visited the Deutsche Bank’s cashiers’ hall. Bank staff members asked many of the athletes whose names were on everyone’s lips for their autographs, which they inserted into a richly illustrated guest book. The name of one athlete who signed there is still well known today all over the world. With three Olympic victories in the two sprinting categories and the broad jump, he was the outstanding competitor of the Berlin Games. “Jesse Owens 100 + 200 meters broad jump U.S.A.” is written in gracious letters at the upper edge of a piece of paper numerous other athletes had also signed, such as the Argentinean Guillermo Lovell (winner of the silver medal in heavyweight boxing), the Australian John Patrick Metcalfe (winner of the bronze medal in the triple jump), the Canadian Howard McPhee (participant in the 100 and 200 meter sprints), the Japanese Noboru Tanaka (participant in the high jump), the Latvian Janis Dalinsch (participant in the 50-kilometer walking) and the Mexican Luis R. Casillas (participant in the modern pentathlon).

Only the names of the female Olympic participants are missing among the collected autographs. The reason for this is simple: Female athletes were not accommodated in the Olympic Village and were no allowed to enter it, either. The women’s accommodations were in what was called the “Friesenhaus”, a reed-covered cottage-style building, not far from the Olympic Stadium.

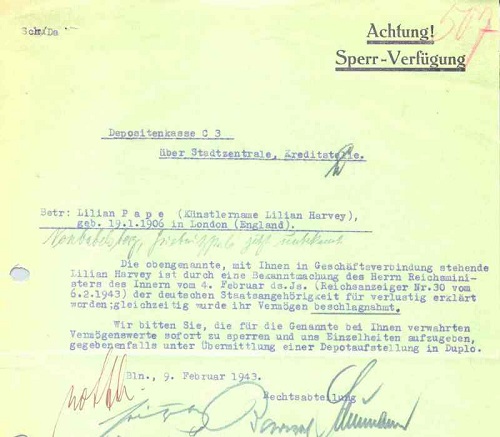

Show content of 09.02.1943 - Film star Lilian Harvey and Deutsche Bank

Please note!

Please note!

Blocking order

Branch office C 3 via city headquarters, loans office

Concerning: Lilian Pape (stage name: Lilian Harvey), born in London (England) on 19th January 1906.

Neubabelsberg, Griebnitzstr. 6, present address unknown

As a result of a notification by the Reich Minister of the Interior dated 4th February of this year ("Reichsanzeiger" [Reich Law Gazette] No. 30 of 6th February 1943), the above-mentioned Lilian Harvey who has a business relationship with you, has been deprived of her German nationality; her assets have simultaneously been confiscated.

We request you to issue a block on assets held by you for the above-mentioned Lilian Harvey with immediate effect and to provide us with details, where necessary by forwarding a statement of securities in duplicate.

Berlin, 9th February 1943

Legal Department

Comment

On February 6, 1943, a list of names was published in the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (German Reich Law Gazette). All persons mentioned on the list were denied German nationality and their assets seized. Almost all of the individuals who were expatriated and deprived of their assets in this way were unknown Jewish men and women. However, one name on the list did not fit into this group: "Lilian Pape (stage name Lilian Harvey)". Less than ten years previously, Lilian Harvey was the star of German cinema. Her roles alongside Willy Fritsch in "Drei von der Tankstelle" (Three from the Filling Station) (1930) and "Der Kongress tanzt" (Congress Dances) (1931) remain unforgotten to this day. Now she was accused of "being hostile to the German people and engaging in subversive activities". She had "made hateful remarks about the leadership of the German Reich and the German people" and continuously passed herself off as English.

The seizure of her assets had a direct impact on Lilian Harvey's account relationship with Deutsche Bank. Her accounts, which were held at branch office C3 on Kurfürstendamm 92 in Berlin, were immediately blocked and placed under the supervision of the competent state authorities. Using the document attached, the Legal Department of Deutsche Bank instructed the branch responsible to block the accounts and to notify it of the assets held. The assets at hand had to be paid over to the German Reich at a subsequent date.

Deutsche Bank's relationship with Lilian Harvey, which ended in 1943 as a result of an indiscriminate administrative act by the Nazi regime, had begun in happier times. Born as Lilian Pape in London in 1906, the actress grew up in a German-English family. Her father, Walter Pape, a banker from Magdeburg, settled in London after his marriage to an Englishwoman and worked for many years at the Deutsche Bank London Agency. A colleague of his at the time recalled some years later, "our colleague, Walter Pape, whom we called Pepi, managed the current account ledger and was a very nice man, short but good-looking and very musical. He is the father of our popular film star Lilian Harvey, who most likely inherited her talent from him."

At the beginning of the First World War, the Pape family visited Magdeburg but was unable to return to London owing to the outbreak of war. The family settled in Berlin, where Lilian took her Abitur (German final secondary-school examination) in 1923. She acted in her first film roles as early as the following year and soon progressed to leading roles. During this time, she changed her name to Lilian Harvey, her grandmother's maiden name. After moving to Germany's largest film company, Ufa, she quickly become the country's most popular film star. Songs featured in her films, "Liebling, mein Herz lässt Dich grüssen" (Darling, my heart sends its love to you) and "Das gibt’s nur einmal, das kommt nie wieder" (It can only happen once - and even more so) became well known hits.

In 1932, she signed a contract with 20th Century Fox and moved to Hollywood. However, by 1935 she was back in Germany, where the Nazis had since come to power. She was able to carry on from her earlier successes in a number of films. Nevertheless, in spite of her stardom, her relationship to the Third Reich remained a distant one. In 1939, Harvey emigrated to France. Owing to the threat of occupation by German troops, she fled to the United States, where she settled in Hollywood. She was never to star in a film again, but became a much sought-after stage actress. After the war ended, she returned to the South of France, where she died in 1968. As reparation for her seized assets, in 1957, she received a life-long pension from the Federal Republic of Germany.

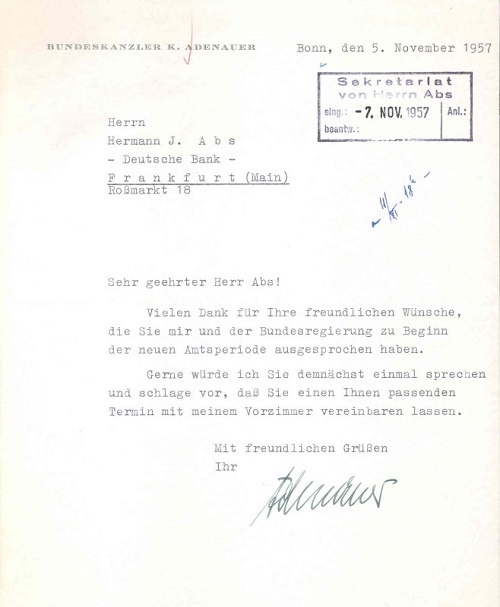

Show content of 05.11.1957 - Germany’s Chancellor and his Banker - Konrad Adenauer and Hermann J. Abs

German Chancellor K. Adenauer

German Chancellor K. Adenauer

Bonn, November 5, 1957

Mr.

Hermann J. Abs

– Deutsche Bank –

Frankfurt (Main)

Rossmarkt 18

Dear Mr. Abs!

Thank you very much for your cordial wishes, which you expressed to me and the German Federal Government at the beginning of our new period of office.

I would like to talk to you soon and propose you have an appointment that suits you arranged with my secretariat.

Yours sincerely,

[signed: Adenauer]

Comment

The leading role in German banking, which Deutsche Bank took on soon after its foundation, brought the men at its head into contact with the top politicians of the country, to a certain degree automatically. And thus, for example, the first Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors, Georg von Siemens, made sure he had obtained Bismark’s diplomatic support before he dedicated himself to the bank’s railway construction venture in the Ottoman Empire. Alfred Herrhausen and Helmut Kohl were friends; in speaking to each other they used the informal German form for "you", that is "Du".

But if you consider the amount of political influence that any given Spokesman of the Board of Managing Directors of Deutsche Bank was in a position to exercise vis-à-vis a German government leader, then without a doubt Hermann J. Abs’s advice had the greatest weight with Konrad Adenauer.

The politician, whose career appeared to be at an end already in 1933, and the banker, who was 25 years younger, crossed paths for the first time directly after the end of the Second World War, when both were appointed members of the supervisory board of RWE, a leading power utility company in Germany. During the first few post-war years, whereas Adenauer quickly became the figure for integration in the newly founded political party of Christian Democrats (CDU), taking on his party’s leadership in the Land Parliament in North Rhine-Westphalia, Abs was basically condemned to inactivity. Only in 1948 – once denazification was completed, clearing his name, and the approval was given for West Germany to be included in the European reconstruction program – Abs was appointed to direct the Reconstruction Loan Corporation (KfW), one of the key institutions of the economic new beginning in the three Western zones of occupation. From this time on, he was one of the inner financial and economic advisors of the man who would be elected in September 1949 to be the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Soon afterwards, when the regulation of Germany’s foreign debt came onto the agenda, Adenauer appointed Hermann J. Abs to be the chief negotiator for the German delegation. The lengthy and complicated negotiations with Germany’s international creditors became his political masterpiece, in which, as a result of the London Foreign Debt Agreement of 1953, West Germany’s creditworthiness abroad was successfully restored.

At the latest since the negotiations on Germany’s foreign debt, Abs was a member of the inner circle of power in the capital Bonn. He was not just a regular guest in the German Chancellery, but his professional advice was also requested on several occasions at cabinet meetings. In 1952 Adenauer even wanted to appoint him to be Foreign Minister. When Adenauer’s intention was met with opposition both in the Chancellery and in the CDU party, he continued to hold the two offices of Chancellor and Foreign Minister.

The basis of trust between Adenauer and Abs did not end as a result of the retraction of this proposed nomination. With their shared Rhineland origins, they maintained their extraordinary friendship in the years that followed: Adenauer, who stood at the helm of the ship of state up until 1963, and his advisor Abs, who returned in 1952 to “his” Deutsche Bank and who was always to retain his independence, despite his direct access to political power. It can be seen from the letter reproduced here that, even after the tremendous success with which he won the absolute majority in the German Parliamentary elections of 1957, Adenauer continued to seek the advice of Abs.

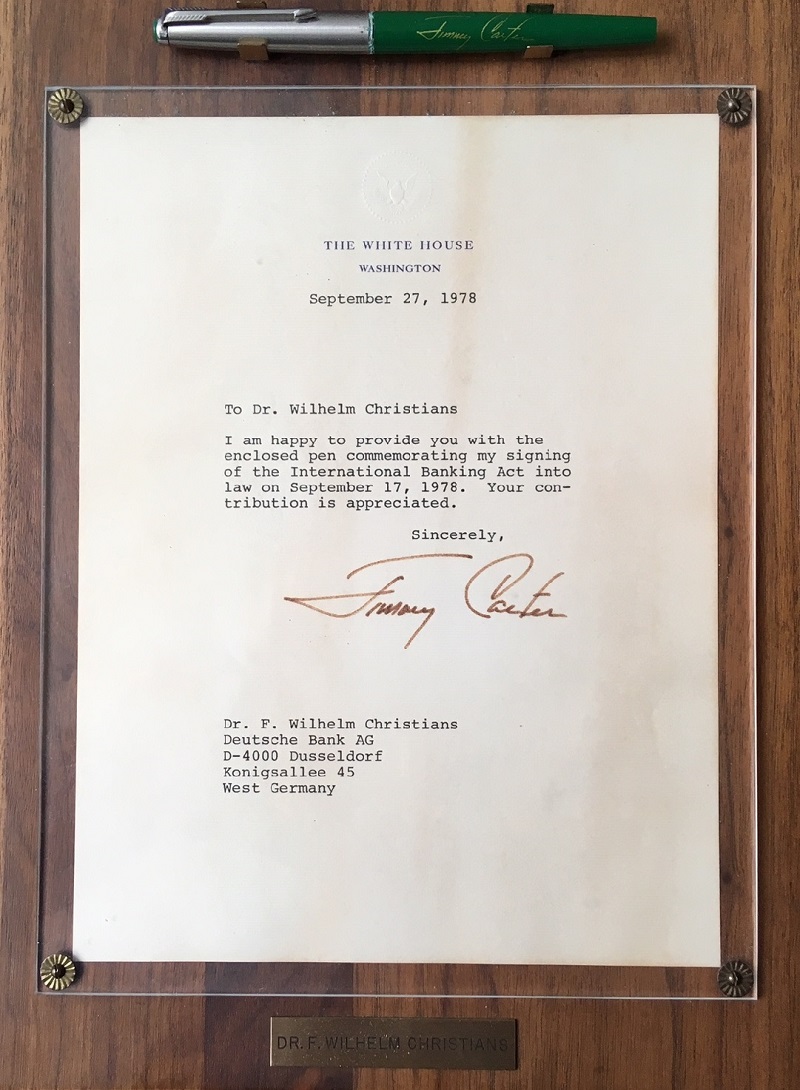

Show content of 27.09.1978 - Jimmy Carter's Pen and the International Banking Act

THE WHITE HOUSE

THE WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON

September 27, 1978

Dr. F. Wilhelm Christians

Deutsche Bank AG

D-4000 Dusseldorf

Konigsallee 45

West Germany

To Dr. Wilhelm Christians

I am happy to provide you with the enclosed pen commemorating my signing of the International Banking Act into law on September 17, 1978. Your contribution is appreciated.

Sincerely,

Jimmy Carter

Comment

In a personally signed letter, Jimmy Carter (*1924), the 39th President of the United States (1977 to 1981), thanked Deutsche Bank's Spokesman of the Management Board, F. Wilhelm Christians (1922-2004), for his contribution to the enactment of the International Banking Act of 1978 in his capacity as President of the Association of German Banks (Bundesverband deutscher Banken), in which Christians had exchanged views with key participants in the banking reform in Washington the previous year. A pen with Jimmy Carter's handwritten name was attached to the document, which was affixed to a solid block of wood, commemorating the signing of the law.

The International Banking Act was intended to provide a comprehensive framework for the regulation and supervision of foreign banking in the United States for the first time. Until the early 1970s, foreign banks in the U.S. were mostly specialized in foreign trade financing. Between 1972 and 1977, the number of foreign bank offices doubled to 210. Although this growth was dramatic, it was still relatively small compared to US banks' exposure abroad. The aim of the law was to grant foreign banking institutions the same rights, obligations and privileges as domestic banks, while strengthening domestic banks. They felt increasingly threatened by the growth of foreign banking activity and worried about the impact on the domestic banking sector and the monetary policy of the United States. At the same time, however, foreign retaliation was feared for overly restrictive measures. Such retaliation would have been devastating for the major US banks, as foreign banking was an important source of income.

The International Banking Act of 1978 placed all U.S. branches of foreign banks under the jurisdiction of U.S. banking regulations with required reserve ratios and U.S. accounting and regulatory standards, while at the same time providing banks with deposit insurance and simplification to establish branches within the United States. Foreign institutions could thus establish branches on an equal footing, but were obliged to designate a particular state as their "home state" and no subsidiaries could be acquired outside that home state. However, these restrictions could be circumvented by a "grandfather clause" if a foreign bank had already obtained its US licence before 27 July 1978.

On July 15, 1978, just twelve days before the end date of the clause, Deutsche Bank received a license from the State of New York Banking Department to establish a branch in Manhattan. A coincidence or a clever move?

Already in the second half of 1977, internal bank reports had recommended applying for the license before the International Banking Act came into force. The decision came at a time when Deutsche Bank's overall strategy was to be represented with its own branches in the world's major financial centers. In the U.S., where it had already been doing business for about a hundred years, it had not been present under its own name. Against the background of the imminent adoption of the International Banking Act and the participation of leading representatives of Deutsche Bank in this process, the "punctual" application for the license for the New York branch, which was finally opened on April 30, 1979, testifies in any case to a clever timing.