Milestones

Stories pertaining to the history of Deutsche Bank

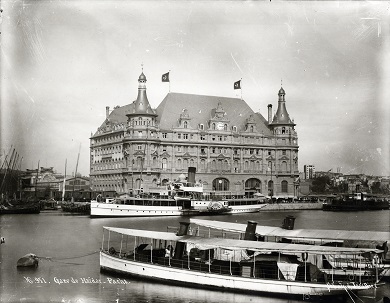

Show content of Baghdad Railway

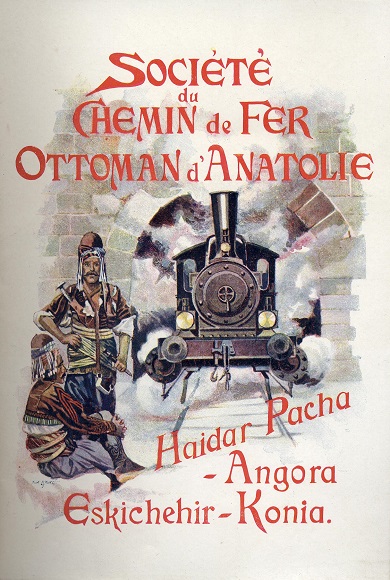

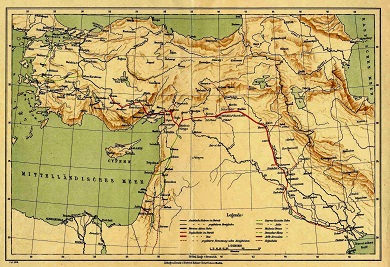

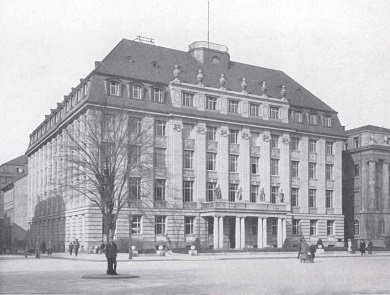

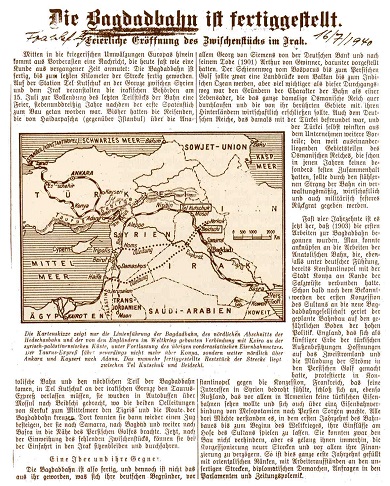

One of the best known events in economic history is undoubtedly the construction of the Baghdad railway, in which Deutsche Bank participated as financier and operator. Hardly any other railway caused as much excitement before the First World War as this one, which was planned to run from Haydarpasha Station in the Asian part of Istanbul to the Persian Gulf.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II had approached German financial circles in 1888. His proposition was to build a new railway that would open up, economically and strategically, the gigantic Turkish Empire from the Bosporus to Schatt el Arab.

After some initial skepsis, Deutsche Bank agreed to take part in the project. In October 1888 it received concessions for the first sections from Haydarpasha to Ismid and then on to Ankara.

The building work was carried out mainly by the Frankfurt firm of Philipp Holzmann.

Despite the difficult terrain, work progressed quickly. By the end of 1892, the almost 600-kilometre stretch to Ankara had been completed. The line to Konya, covering a further 400 kilometres, was opened in 1896.

Negotiations on the continuation of the line from Konya to Baghdad and then on to the Persian Gulf filled the subsequent years. The railway was in the headlines time and again owing to the disputes with the other major European powers whose political and economic interests were affected by it. "I couldn't care less about the concession or the entire Baghdad railway", said Georg von Siemens, Spokesman of Deutsche Bank's Board of Managing Directors, in 1898, venting his anger. The many political obstacles made him so impatient with the Baghdad railway project that he even offered it to the Russian Minister of Finance, Witte, at the beginning of 1899. Witte declined with thanks.

The construction and operating concession for the railway was transferred to a separate Turkish-law stock corporation, the Anatolian Railway Company.

In March 1903, Deutsche Bank finally signed the so-called "Baghdad Concession".

Construction of the railway line continued from Konya across the Taurus and Amanus Mountains to Mosul, Baghdad and Basra in stretches of 200 kilometres at a time.

By the beginning of the First World War, roughly 600 kilometres had been completed. But Baghdad was still 650 kilometres away. War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire brought the building work to a halt. The final section of the Baghdad railway was eventually built by the Iraqi State during the years from 1936 to 1940. The first train travelled from Istanbul to Baghdad on July 15, 1940.

Show content of Big Clients

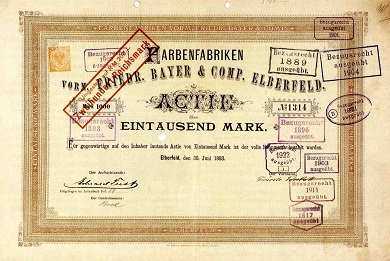

In Deutsche Bank's early years, trade finance and public-sector bond issuance were the most important fields of business. At the same time, the rapid growth of industry created a new and interesting group of customers. Bank services, such as current account business, were the basis of these connections. The introduction of equities and bonds of the big industrial enterprises was the crowning development in this new area of business.

The bank was particularly successful in burgeoning sectors such as chemicals and electrical engineering. In 1885, it introduced the shares of Friedrich Bayer AG, founded just a few years earlier, on the Berlin Stock Exchange and subsequently participated in all of the company's share and bond issues.

In the electrical engineering industry, Deutsche Bank was first involved with Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG).

After Siemens had been transformed from a family enterprise into a joint-stock corporation in 1897 with the help of Deutsche Bank, business relations with this company also continued to intensify. The largest project realized by the bank jointly with Siemens was the construction of the Berlin overground and underground railway.

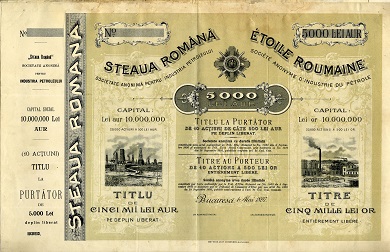

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the establishment of new transport routes and the growing demand for energy aroused the banks' interest in oil. In 1903, Deutsche Bank acquired the Romanian oil company Steaua Romana. After the end of the First World War, it had to sell the company to an Anglo-French consortium of banks.

In the years between the wars, Deutsche Bank expanded its business activities to new sectors such as the film industry, vehicle manufacturing and air transport. It was therefore linked right from the start with world-famous brands such as Ufa, the film company, Daimler-Benz and Lufthansa.

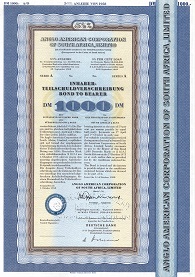

Owing to the weakness of the German currency, the German banks had been excluded from the international capital markets since 1914. It was not until 1958 that a bond in German currency was launched for a foreign issuer on the German capital market for the first time since the beginning of the First World War.

Show content of Break-up and Reconstruction

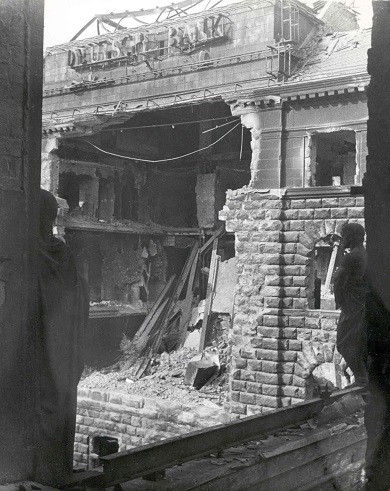

“A dark day in the history of Deutsche Bank. It has been posted that the employees in Berlin are being temporarily laid off, those exempted from this will be notified. It is recommended that new employment be sought elsewhere.” This diary entry by one of Deutsche Bank’s senior representatives from June 16, 1945, marks the all-time low in the bank’s development.

75 years after its establishment, at the end of the Second World War Deutsche Bank’s very existence was under threat.

The head office in Berlin, the very heart of the company, was closed down on the orders of the Soviet occupying power. This measure was backed by an ordinance by the City Council of Berlin which forbade the owners of banking houses and bank directors to conduct financial business.

From this point on, Deutsche Bank was classified as an “institution in abeyance” and was permitted to perform only very restricted activities for the purpose of dissolving and terminating business. In the course of 1945 and 1946, a similar fate was to meet all the other branches within the area that later became the German Democratic Republic; their business was taken over by the now state-controlled banking sector.

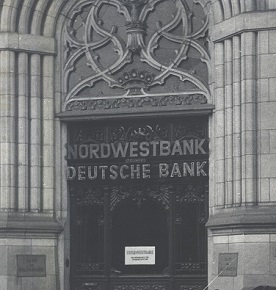

In the Western zones, the bank was able to continue it business activities. It had established an emergency administration shortly before the end of the war. A management team in Hamburg temporarily took over coordination of bank-wide matters following the closure of the head office in Berlin.

But soon the bank would be prohibited from acting as a single institution in West Germany, too. The Allies, in particular the Americans, felt that the big banks had been too closely involved in the National Socialist military build-up and the war-time economy.

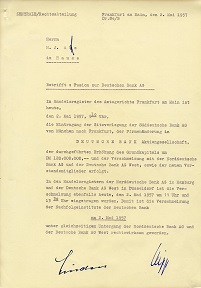

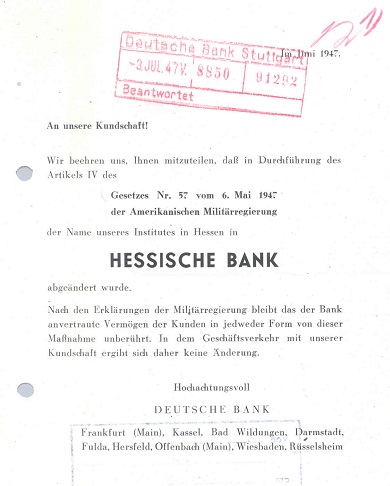

On May 6, 1947, the U.S. Military Government issued Law No. 57 for its zone of occupation; in October of the same year the law was implemented in the French zone and in April 1948 in the British zone.

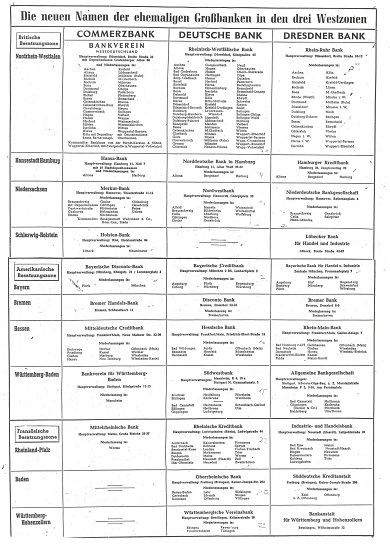

Conducting banking business under the name of “Deutsche Bank” was now prohibited. The branches of the former Deutsche Bank had to be transformed into administratively independent banking enterprises operating at regional level. So it was that ten institutions were created, some of which briefly revived the names of predecessor banks which had gone into disuse decades previously following mergers.

These sub-banks were officially prohibited from any form of cooperation across the federal state boundaries. Custodians were appointed to oversee them.

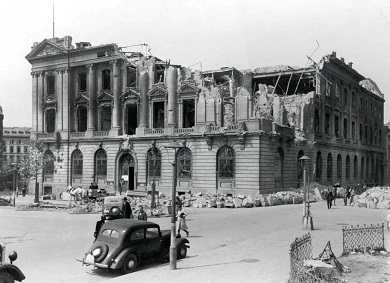

But it was not only because of the political obstacles that bank employees faced major challenges on a daily basis.In many of the larger cities the bank’s buildings had been seriously damaged if not completely destroyed in air raids. In most cases, only the vaults had survived intact. In the initial years after 1945, banking operations were conducted under some very adventurous makeshift arrangements.

Reunifying the bank remained top priority at all times. Together with the successor institutions of Dresdner Bank and Commerzbank, which had also been divided up, attempts were made to overcome the restrictions placed on the former big banks. After the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany, the bank managed to achieve reconstitution in two stages.

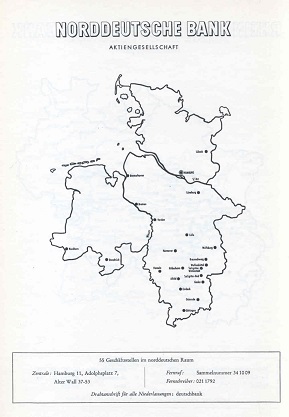

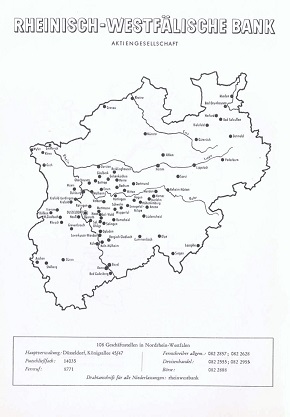

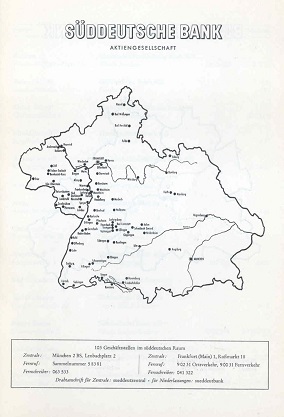

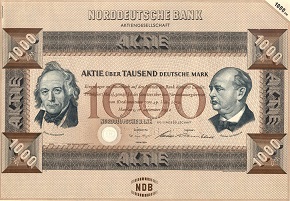

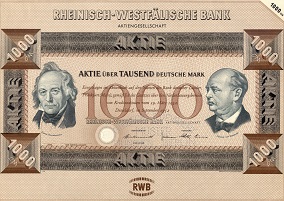

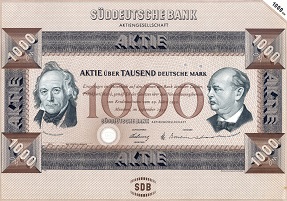

In September 1952, as an interim solution three institutions were established: Rheinisch-Westfälische Bank in Düsseldorf, Süddeutsche Bank in Frankfurt and Munich, and Norddeutsche Bank in Hamburg. They were hived off from the old Deutsche Bank.

Unlike the former sub-banks, whose commercial scope had been severely restricted, these three successor institutions were stock corporations and were able once again to conduct strategic business operations. The sister banks held frequent joint meetings in which they coordinated business and personnel policies. In 1955, they were already acting as “Deutsche Bank Group”.

The “Act to remove the restriction on the regional scope of credit institutions” ultimately cleared the way for complete reconstitution of the three successor institutions, which amalgamated at the end of April 1957 to become Deutsche Bank AG.

On May 2, 1957, the reconstituted bank was entered in the Commercial Register in Frankfurt am Main, seat of the company’s new registeredoffice. Back under one roof, bearing a name which had stood the test of time, Deutsche Bank could begin to resume a leading position in the now prosperous post-war Germany.

Show content of Foundation

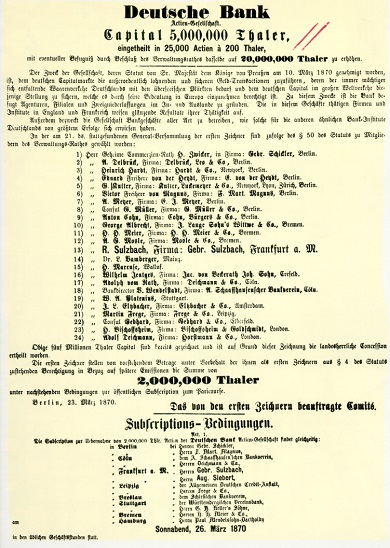

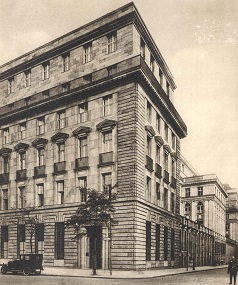

The idea leading to the formation of Deutsche Bank in 1870 took shape in times of upheaval in the banking sector. Industry's financial needs were growing in the wake of industrialization and called for new developments in traditional banking business. In Berlin, a number of private bankers were open to new ideas, and the driving force behind them was Adelbert Delbrück, head of the banking house Delbrück Leo & Co. Together with Ludwig Bamberger, politician, banker and expert in monetary theory, Delbrück is regarded as the "true founder" of Deutsche Bank.

The name "Deutsche Bank" was soon chosen and was programmatic for the bank itself. On the eve of the foundation of the first national German state, it was the initiators' declared intention to create a German bank, which had its headquarters in the capital of the politically and economically predominant Prussia and would release Germany's foreign trade from its dependence on English and French banks. The new bank was to specialize in foreign trade, as underlined in the Articles of Association approved by the Constitutive Assembly on January 22, 1870. “The purpose of the company is the transaction of banking business of all kinds, in particular the promotion and easing of trade relations between Germany, the other European countries and overseas markets."

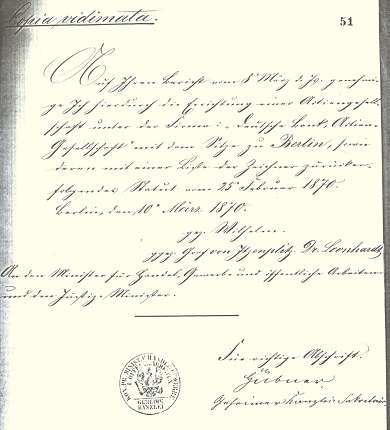

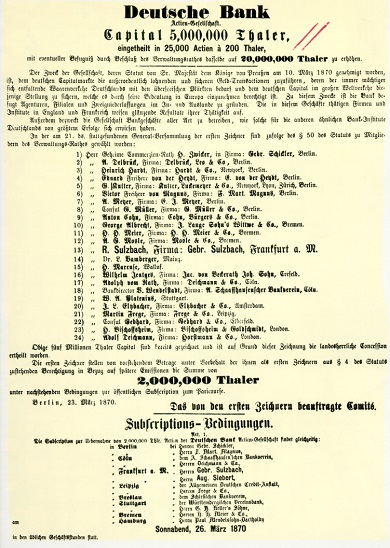

But there were still political obstacles to be surmounted. In Prussia, namely, all previous applications to set up joint stock banks had been turned down by the government. This time, however, the decision was different thanks to the founders' reputations and the importance attributed to the bank project for Berlin as a major financial centre. On March 10, 1870, King Wilhelm I signed the concession to set up the company "Deutsche Bank, Aktiengesellschaft". This document is considered to be the actual "birth certificate" of Deutsche Bank.

The door was now open for the first general meeting of shareholders, at which 76 shareholders subscribed the share capital of 5 million talers. A few days later, on March 24 and 25, 1870, the initial buyers offered shares totalling 2 million talers for public subscription.

The first general meeting of shareholders elected a 24-strong Board of Directors from among the shareholders. One of its first tasks was to determine the bank's future management.

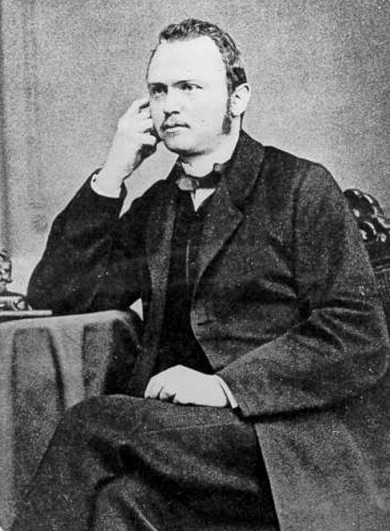

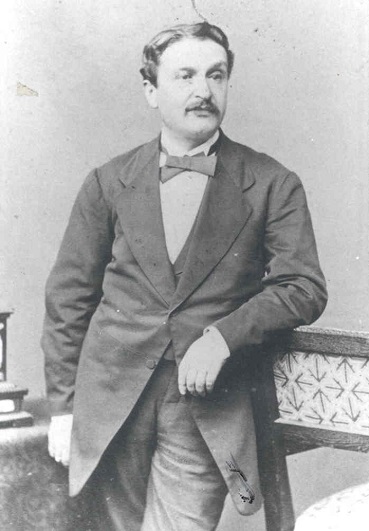

The choice fell on Georg Siemens, a young lawyer who had given proof of his abilities in contract negotiations on the construction of a telegraph line in Persia he had conducted for the company Siemens. Over the next three decades, Georg Siemens was to decisively shape the bank’s evolution. At his side was Hermann Wallich, who had previously been manager of the Shanghai branch of Comptoir d’Escompte and who joined Deutsche Bank’s Management Board in the autumn of 1870.

Wallich was member of the bank’s senior management until 1894, serving over the years with Georg Siemens, Rudolph Koch and Max Steinthal on the Management Board.

Show content of Jubilee

150 years ago Deutsche Bank was founded to promote and facilitate trade relations between Germany and other countries and thereby to connect worlds. Deutsche Bank’s round birthdays have come during very contrasting periods – ranging from the optimism about a bright future to the chaos of war. On two occasions already there were no celebrations at all – and on one occasion a Rhine river cruise ship was involved. Here is a summary.

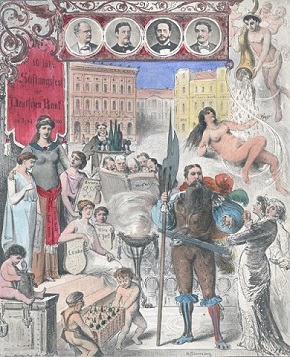

1880: When a company is founded, its founders are unlikely to spare much thought for future anniversaries. Nevertheless, the emerging Deutsche Bank was steeped in the anniversary culture soon, when it took its 10th anniversary as an opportunity for a retrospect. What has come down through the years is a colourful commemorative leaflet describing developments until then and a Deutsche Bank Jubilee March, “respectfully dedicated to the latter’s Directors”.

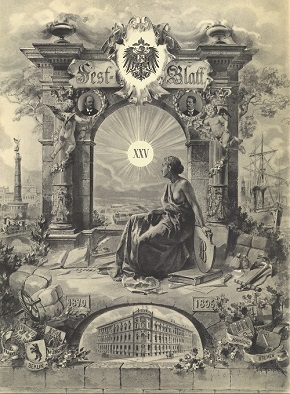

1895: Deutsche Bank also celebrated its 25-year anniversary with great pomp: business in Germany and abroad had been excellent and it had become the leading German bank. The cover of the ornate anniversary brochure depicted Deutsche Bank as a lady from an ancient era sitting in front of a classical "arch of triumph” window structure.

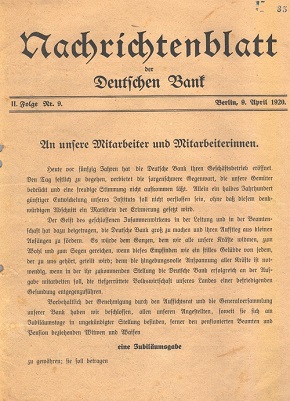

1920: Deutsche Bank’s 50th anniversary was overshadowed by the lost war, the catastrophic conditions in the young Weimar Republic, a depreciating currency and an uncertain future. “We are forbidden from celebrating this day in festive manner by times which are fraught with grave concerns, which weigh heavy on our hearts and prevent any feelings of joy from arising”, wrote Deutsche Bank’s Management Board in the foreword to a extremely unostentatious “commemorative leaflet” on April 9, the anniversary of its first day in business.

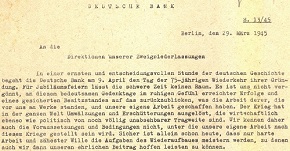

1945: But worse was still to come: the 75th anniversary in April 1945 coincided with the final apocalyptic weeks of the There were no celebrations of any kind. As usual, employees received a bonus, but in the light of the existential crisis at the time, it was insignificant. Writing from a Berlin that was still in the throes of fighting, the Management Board merely sent a short letter to the few branches in contact with the Group’s top management.

1970: The prospect of Deutsche Bank ever celebrating its centenary would have appeared rather remote in 1945. But after years of partition, the bank’s centenary celebrations came in a phase in which domestic business was expanding strongly and the bank’s return to the international markets was in the offing. Deutsche Bank therefore celebrated its centenary on April 9, 1970 not only at the head office in Frankfurt: nearly every Deutsche Bank branch arranged special events for this major anniversary. On the following day the entire Management Board took international guests for a steam boot cruise on the Rhine river.

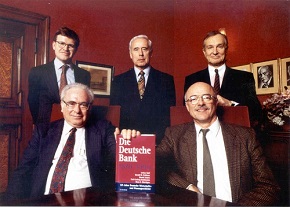

1995: In the year of its 125th anniversary, Deutsche Bank could look back on considerable business growth and major expansion of its international activities. The festivities again took place in Frankfurt, this time on March 10, the anniversary of the granting of its concession, at the Alte Oper concert hall. In advance of the occasion, the Management Board had commissioned five historians to write a history of the bank – and to comprehensively investigate the responsibility of the bank during the Nazi regime.

2020: Deutsche Bank had to postpone the 150th anniversary ceremony that was due to be held on March 21 in the Schauspielhaus am Gendarmenmarkt – just a stone’s throw from the bank’s first premises – to help slow the spread of the coronavirus. On March 21, 1870, the 76 shareholders who had provided the 5 million talers (15 million marks) of initial capital convened in Berlin for the inaugural General Meeting. There they elected the bank’s first Supervisory Board.

To mark the bank's 150th years in existence the book "Deutsche Bank. The Global Hausbank 1870-2020" is launched right now. The distinguished economic historians Werner Plumpe, Alexander Nützenadel and Catherine R. Schenk scrutinised how Deutsche Bank developed during various phases of globalisation.

To mark the bank's 150th years in existence the book "Deutsche Bank. The Global Hausbank 1870-2020" is launched right now. The distinguished economic historians Werner Plumpe, Alexander Nützenadel and Catherine R. Schenk scrutinised how Deutsche Bank developed during various phases of globalisation.

Show content of Logo

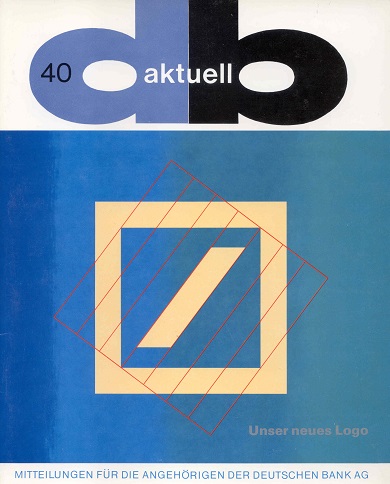

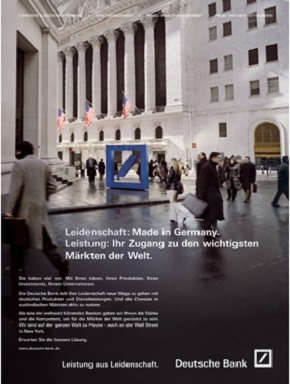

“The logo is a trademark, a diagonal and a square. Long live our new logo!” The Deutsche Bank staff magazine enthusiastically greeted the introduction of the new logo at the end of 1973.

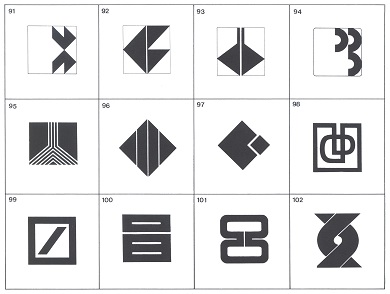

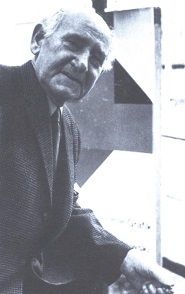

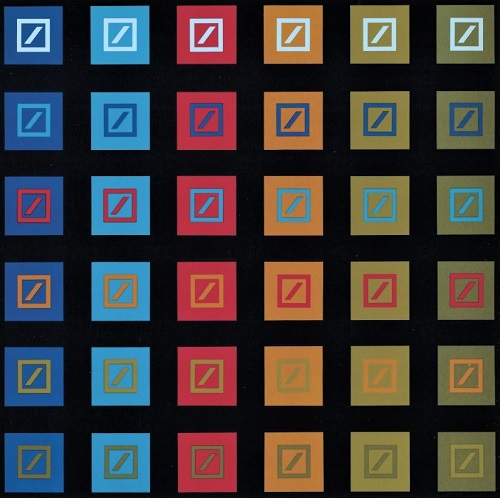

In July 1972, Deutsche Bank had commissioned eight internationally renowned graphic artists to design a modern logo. A decision was reached in spring 1973. From the 140 drafts, the bank finally chose the design by artist and graphic designer Anton Stankowski, the diagonal in the square. As early as the 1920s, the grand master of Constructivism and a pioneer of graphic design had earned himself a reputation around the world with his successful advertising campaigns.

As studies had shown that the colour blue inspired confidence and implied reliability, the Management Board decided to have the logo in blue. With the new logo, the bank also changed the design of its company name. In contrast to the former majuscules, the bank now opted for small lettering in the “Univers” font.

The logo was presented to the public at the annual press conference in April 1974. Although it was just the first step, the logo was a visible symbol of a programme designed to harmonize the bank’s image, which not only began to standardize the appearance of all the bank’s printed matter but also the structure of its branches and offices.

At the time the new logo was introduced, the last redesign had taken place decades earlier. When the bank was established in 1870, the company logo had not played any role at all to start with. Even the company name, “Deutsche Bank”, could be written in different fonts within the same document. By the turn of the century at the latest, the “imperial eagle” with the initials DB had become established. The eagle was very similar to the Prussian and the German national imperial eagle, which contributed to the fact that the bank was often regarded as a “state institution”.

The name “Deutsche Bank” also meant that the bank was often mistaken for the German central bank. After the merger with Disconto-Gesellschaft in October 1929, the heraldic eagle, which at the time still had a rather distinct Wilhemine air, was re-stylized following the New Objectivity movement.

It did not appear so much in the bank’s general advertising but was rather intended to give checks, share certificates, savings books and letters of credit a greater appearance of value. Any colour was still possible at this time: black, blue, red, even green or yellow.

In 1937, Deutsche Bank started using a typical letter-based trademark, “DB” in an oval. The stylized eagle was still used, however, and existed in parallel alongside the DB oval.

After the Second World War, when Deutsche Bank was spilt into ten regional institutions from 1947 to 1952, the regional “sub-banks” all consistently used the letter-based logo – with their own initials – in the style of the former “DB in an oval”.

The three successor institutions formed in 1952, Norddeutsche Bank, Rheinisch-Westfälische Bank and Süddeutsche Bank, also used letter-based logos. But these had a completely new style. Chunky block letters replaced the previously rather delicate lettering and were flanked by coin edges – which some mockingly referred to as “jaws”.

In 1957, when Deutsche Bank was reconstituted, it simply started using its old logo again, DB in an Oval and the stylized eagle; in this context, a sign of its commitment to continuity and tradition.

However, in the 1970s, a time of fast-moving and drastic change, a visual symbol language rapidly gained popularity. Deutsche Bank recognized that it would have to change the way it presented itself to the public if it were to avoid coming across as old-fashioned – especially abroad where it was just beginning to develop an international presence.

The search was on for a logo that could be used around the world whatever the language or script. Hence the competition and Stankowski’s diagonal in the square. Coinciding with the launch of the new logo, a survey was conducted among employees to find a name for the logo and the term “sign post” came out the winner. This term was also used in the first advertising campaigns for the new logo.

In the international Deutsche Bank Group of today, the diagonal in the square is usually interpreted as a symbol of dynamic growth in a secure environment. Through its timeless simplicity, the logo has achieved a high level of recognition worldwide.

Soon after the launch of the logo, employees began to play with the logo’s form. Since the turn of the 21st century, the design potential inherent in Deutsche Bank’s trademark has been exploited to a significantly greater degree. In 2005, a three-dimensional logo was the centre of a global advertising campaign.

In 2010, Deutsche Bank began to use the figurative mark separately from the word mark. The freestanding logo was to create the basis for a contemporary brand management. Based on the idea of colour diversity, Deutsche Bank showed the logo in various unusual colour combinations for advertising purposes.

In the "BrandSpace" of the Deutsche Bank headquarters in Frankfurt am Main, which was set up in 2011 for a decade, the logo was displayed in sculptural form. The logo was presented in sculptural implementation and large-format media installations.

In 2017, Deutsche Bank decided to revise its brand elements, from typography, visual language and colour spectrum to the claim. From now on, for example, the logo no longer had to be placed rigidly in advertising motifs but could appear in four different positions.

Never at issue was the signet in its familiar shape and form, true to the common maxim in brand management: "Never touch the logo".

In July 2020, an 8.46-metre-high logo was installed on the roof of the football stadium at Deutsche Bank Park in Frankfurt. It is the world's largest representation of the logo.

Almost 50 years after its introduction, the logo still plays a key role in Deutsche Bank's branding strategy.

Show content of Merger with Disconto-Gesellschaft 1929

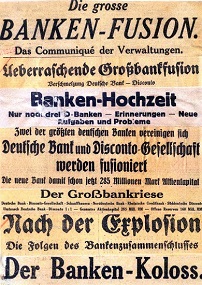

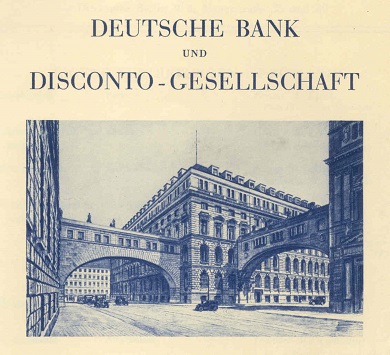

On September 26, 1929, the well-kept secret was unveiled: two of the largest German banks – Deutsche Bank and Disconto-Gesellschaft – were about to tie the knot. In Germany’s banking capital, Berlin, this caused a sensation as the banks had been bitter rivals for many decades. Now the largest merger in German banking history was in the offing. Disconto-Gesellschaft, established in Berlin in 1851, had been the uncontested leader among German banks for a long time. It was only when Deutsche Bank was established 19 years later that a worthy rival began to emerge. Both banks were leaders in the capital market; both had excellent contacts to large-scale industry and international financial circles.

As early as summer 1926, the idea of a merger had been discretely sounded out in the Swiss spa resort Pontresina – to a certain extent on neutral ground. The initiative came from Deutsche Bank. Both banks had recognized that the difficult economic circumstances in the post-inflationary years called for mergers to ensure adequate capital provision for the industrial sector and to contain their own administrative costs. But they were still reluctant to take the final plunge. It was only when Deutsche Bank began to look around for alternative partners that the merger project really took off. The main candidate under discussion was Dresdner Bank. In a further meeting in Pontresina in summer 1929 between Oscar Schlitter, a member of the Management Board of Deutsche Bank and Eduard Mosler from Disconto-Gesellschaft’s Management Board, the merger of Deutsche Bank and Disconto-Gesellschaft began to take form. Mosler concluded the talks with Deutsche Bank Spokesman Oscar Wassermann in Berlin. The merger also included the regional banks closely affiliated to the two big Berlin-based banks and with longstanding traditions of their own:

Norddeutsche Bank in Hamburg,

A. Schaaffhausen'sche Bankverein in Cologne

and Süddeutsche Disconto-Gesellschaft in Mannheim, which were part of the Disconto-Gesellschaft group,

and Rheinische Creditbank in Mannheim, which belonged to Deutsche Bank Group.

When news of the project reached the public at the end of September 1929, it was greeted with great surprise. The reaction from the press was mixed, but the majority were in favour of the merger. One month later on October 29, 1929, the shareholders meetings of both banks approved the merger to “Deutsche Bank und Disconto-Gesellschaft” as the new bank was now officially known.

Thus, a bank was created which, with 800,000 accounts and 289 branches, was not only by far the largest financial institution in Germany, but could also hold its own against the biggest English and American banks.

This was no love-match, but rather a marriage of convenience. The characters of the two big banks could not have been more different. As a leading representative of Deutsche Bank so aptly put it, “Deutsche Bank was entirely consumed by the commercial spirit. Every big company has a certain tendency towards bureaucracy, but at Deutsche Bank this tendency was repressed as much as possible. At Disconto-Gesellschaft, however, they had conceded to it to a far greater degree. Years earlier, old Carl Fürstenberg from the Berliner Handels-Gesellschaft had said, ‘Disconto-Gesellschaft? That’s not a bank, it’s a ministry.’”

It was the question of profitability, above all, which had clinched the merger deal. By consolidating the broad branch networks and the group managements, the intention was to cut administrative costs perceptibly in the new bank. However, savings were also to be achieved through staff cuts, which were implemented after the merger.

All seven members of Deutsche Bank’s Management Board had a seat on the new management body; of Disconto-Gesellschaft’s eight owners, five joined the new Management Board and three moved to the Supervisory Board. Oscar Wassermann from Deutsche Bank remained Spokesman. The post of Chairman of the Supervisory Board was shared by Max Steinthal from Deutsche Bank and Arthur Salomonsohn from Disconto-Gesellschaft.

The merger actually came at exactly the right time. Just a few days before the executive boards at the two banks gave their blessing to the merger, the New York Stock Exchange had collapsed on “Black Thursday”, October 24, 1929. This was to be the start of the Great Depression, which would later see German banks plunge into their deepest crisis ever, in some cases, coming under heavy state influence. However, “Deutsche Bank und Disconto-Gesellschaft”, weathered this crisis relatively well – not least thanks to the strength which it had gained from the merger. The cumbersome double-barrelled name was not to enjoy a long future. The rather unattractive sounding nickname which was so widely used in the economic press, “DeDi bank”, was extremely unpopular in the new bank. Thus, in October 1937, the bank officially dropped the second part of its name and from then on was known just as “Deutsche Bank”.

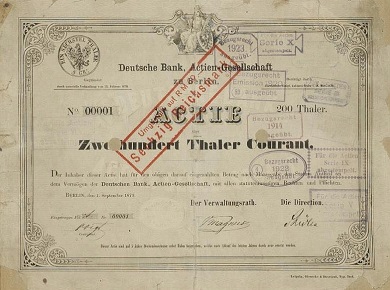

Show content of Share

For one and a half centuries, Deutsche Bank’s share has been part of German bank and stock market history. Deutsche Bank was founded in the legal form of a stock corporation in 1870 in Berlin. At that time, this still required the approval of the Prussian King. This requirement stemmed from the fear of the speculation surrounding what were called “paper banks”, which had been founded in a few cases primarily to achieve quick gains through increasing share prices for the initial subscribers, who then left the company on its own.

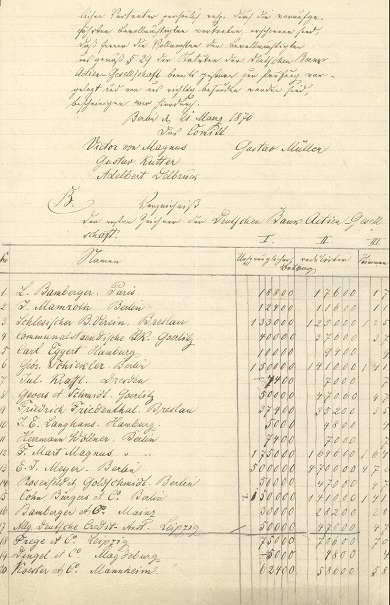

Shortly after the concession was granted on March 10, 1870, the first general meeting of Deutsche Bank took place, attended by 24 people, who represented the majority of the total share capital of 5 million talers.

The list of initial shareholders comprised in total 76 names. This group of “original shareholders” were mainly representatives of private and joint stock banks. Ludwig Bamberger, one of the initiators of the bank’s foundation, was at the top of the list of subscribers. And also Georg Siemens, who was to become the leading figure at Deutsche Bank, was a member of this group of shareholders, subscribing to the relatively modest amount of 5,000 talers.

The Deutsche Bank share started trading for the first time on the Berlin Stock Exchange on May 12, 1870. As payment of the subscription amount took place in three tranches, the initial shareholders were first issued interim vouchers. And it was not until September 1871 that the first regular share certificates were issued – each with a face value of 200 talers.

Unlike government bonds or the securities of industrial companies, whose certificates often displayed complex works of calligraphic art and illustrations of their trades, Deutsche Bank’s securities were kept modest. Up until the period of hyper-inflation, hardly anything changed in the appearance of the Deutsche Bank share, except for the change of currency from taler to marks.

After rampant inflation receded and the Rentenmark, also known as the Reichsmark, was introduced in October 1924, the nominal value in the new currency was stamped onto the shares of the previous issues.

.jpg?language_id=1)

The merger of Deutsche Bank with Disconto-Gesellschaft at the end of October 1929 was an outstanding event in the history of the German bank sector. In their respective general meetings, the two banks preparing to merge had to convince their shareholders of the correctness of this step. The shares issued by the combined institution already in November 1929 showed a completely new image. The main design feature of the new logo of the combined bank was a very stylized eagle, which was to remain in use – with interruptions – until the beginning of the 1970s.

Following the Second World War, conducting banking operations under the name “Deutsche Bank” was prohibited up until 1957. The former shares of the dormant Deutsche Bank, later called the "Old Bank", continued to be traded even after the currency reform of 1948. However, there were no new issues, i.e. the only shares in circulation were the old ones denominated in Reichsmark. With the foundation of the three successor banks – Norddeutsche Bank, Rheinisch-Westfälische Bank and Süddeutsche Bank – DM shares were issued for the first time.

During this period, the old shareholders received what were called remainder ratios, which certified a claim to the confiscated remaining assets of the Old Bank in the GDR and Eastern regions. The fact that these shares were issued in 1952 with a nominal value still denominated in Reichsmark is today considered a curiosity by many.

.jpg?language_id=1)

Following the reconstitution of “Deutsche Bank Aktiengesellschaft”, shareholders were able to exchange securities of the successor banks in 1957 for those of the re-united bank.

Before the Second World War, the Deutsche Bank share was listed only on the domestic stock exchanges. Starting with the beginning of the bank’s business operations in its place of establishment, the share was traded in Berlin and starting in 1880 also in Frankfurt am Main, which became the share’s home stock exchange in 1957. Starting in the 1970s, Deutsche Bank’s Europeanization and internationalization was reflected in the temporary listing of the share in important stock exchanges of the world: Paris in 1974, London in 1976, Brussels in 1978, Tokyo in 1989. The Deutsche Bank share was listed for the first time on the New York Stock Exchange on October 3, 2001. Three weeks after the terrorists' attacks on September 11, this represented a confirmation of the trust in New York as a major financial centre. In this context, the shares were also converted from bearer to registered shares.

Since its foundation, there has never been one dominating shareholder of Deutsche Bank – except for a few years during the banking crisis. Even if, based on share capital, the ratio of private shareholders compared to institutional investors has always been low, the public interest in the Deutsche Bank share price has been steadily increasing, an indicator of success.

The appearance of the Deutsche Bank share has changed significantly over the course of time to such an extent that today’s buyer generally does not actually require any physical certificates, but rather has virtual ones instead; share scrips as well as dividend and renewal coupons are no longer part of the day-to-day handling of shares. The name and legal form of the issuer have, however, remained unchanged since the foundation in 1870.

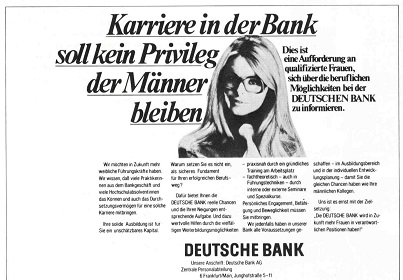

Show content of Women

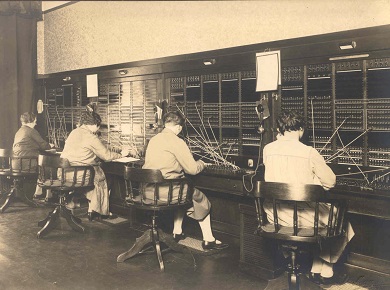

“The employment of females by some of the local big banks ought to be sanctioned” – such was a Berlin bank employee’s opinion of female colleagues working in 1914. Regardless of what caused him to make this remark, at the time, it was extremely difficult for women to even get a foot in the door of a bank. The banking profession remained closed to women until the mid-1920s. A mere four female apprentices were registered in the entire banking industry in Germany in 1878. An apprenticeship in banking required a more advanced school education which, traditionally, had been denied to girls. For this reason, they could only be employed as unskilled staff with low wages. The first female staff were employed as telephonists and stenographers at Deutsche Bank in the period after 1900. Female cleaning and canteen staff had worked at the bank from its foundation.

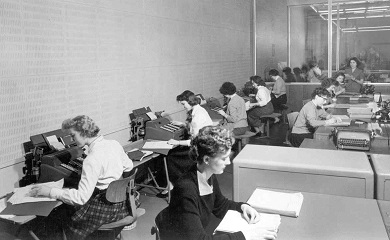

Records of the bank’s first female employees to complete a banking or commercial apprenticeship date back to the year 1914. It was not until the First World War, and the subsequent period of high inflation, with its attendant need for more office staff, that larger numbers of women started working in banks. They were mainly employed to operate office machines, which were in use as a result of increased automation.

In 1927 Deutsche Bank had 8,363 male and 2,082 female tariff employees as well as 711 male and 150 female apprentices on its books. However, there was not even one woman among the 1,245 directors, authorized representatives and other senior bank officers. The global economic crisis of 1929 to 1932 increased the unemployment rate among skilled staff considerably, although more women were affected than men. The National Socialists initially jumped on the bandwagon of rampant resentment towards female employment and spread propaganda that a woman’s role should be restricted to home, family and children. This was to be supported by means of marriage loans if married women gave up their jobs. However, starting in 1936 the Nazi government tried to satisfy the growing need for labour, also for skilled staff, through the employment of women. The employment of all women – married or not – was promoted vigorously by the government during the Second World War. This increased the number of women taking on office jobs. As a result, by the end of 1940, Deutsche Bank employed 3,400 female staff members.

In the decades following the Second World War, the attitude towards women working had changed radically. The percentage of female employees started to steadily rise in the late 1950s, initially due to legal measures to promote equal opportunity, but then to no small part thanks to the emancipation movement. As early as 1956, 45 of every 100 tariff workers employed in the private banking industry in the Federal Republic of Germany were women.

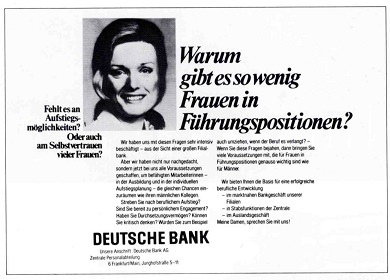

However, it would still take some time before women could rise through the ranks in banking. For this reason, Deutsche Bank, for example, initiated a campaign entitled “Women in Management Positions” in 1973-1974.

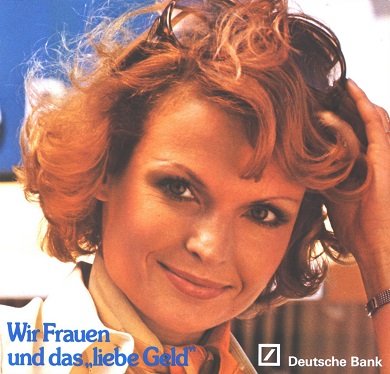

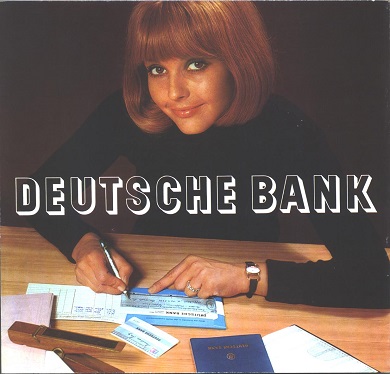

At the same time, banks made an effort to focus more on women as customers and launched a series of advertising campaigns.

In 1971, Hannelore Winter was the first woman to be voted by shareholders onto Deutsche Bank’s Supervisory Board.

In 1988, Ellen R. Schneider-Lenné was the first woman to be appointed to the Management Board of Deutsche Bank – and indeed, of any German “big bank”.

_390.JPG?language_id=1)